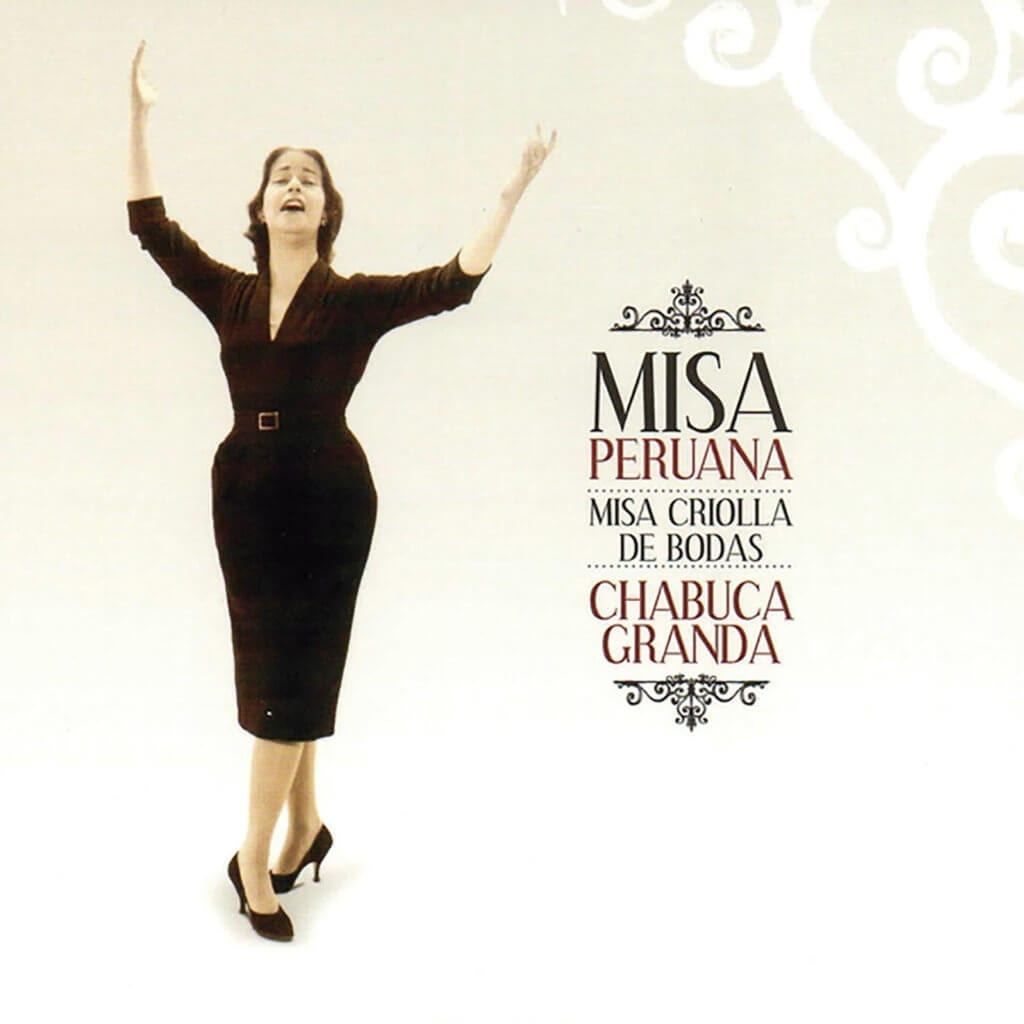

Women’s History Month Series: Chabuca Granda

“Don’t forget me. Sing me,” were singer-songwriter Chabuca Granda’s last words for her friend and mentee, Susana Baca. It wouldn’t be hard to keep her alive through her music. Granda’s legacy would be her songs, her music, her advocacy, and it would be an indelible part of Peruvian musical culture. Her compositions, most notably the anthemic “La Flor De La Canela” were the beginnings of a new era in Afro-Peruvian sounds, with Granda as one of the genre’s most vocal champions. In her decades-spanning career, mostly as an independent artist, she helped bring Afro-Peruvian artists and music into the spotlight, and was an important part of bringing Peru’s black musical heritage back into the public sphere.

Born in the country’s Apurimac region in 1920, Granda’s musical career was somewhat of a second act for her. Her father was a mining executive in the region, but the family moved to Lima when she was still very young. There, she began to take up music, singing in her school’s choir and picking up the guitar. She married young, and music remained a constant for her, playing at home for her husband and children. When Granda and her husband separated, ultimately divorcing in 1952, the music that had only been in the background of her life, began to come more in focus.

She started playing for friends in artist salons, gatherings exploring music, poetry, and politics. Granda played Música Criolla, a traditional Peruvian music combining the country’s African, indigenous, and European influences. Granda was particularly known for her performance of criolla waltzes, which, at that point, were known as a working class music, which as Javier León, director of the Latin American Music Center at Indiana University explains, were “kind of like Peru’s version of country music.” These were songs about heartbreak, nostalgia, and loss. Granda, at first, used the waltz’s basic rhythms, but her lyrics were what made her stand out; they were poetic, celebratory, full of imagery. In 1950, she wrote “La Flor De La Canela,” the song that would become her signature, and would bring these waltzes back into the forefront. These were the sounds and sights of her country, and Granda wanted them to be heard again.

Before the 1950s, música criolla was falling out of favor with the Peruvian upper classes, who started gravitating more toward tangos and American jazz, music that was seen as more “sophisticated” than traditional music of Peru. But by the 1950s, pride in the country’s musical heritage was swelling—particularly in Granda’s circle of upper class, but politically-active, artists and thinkers—and returning to música criolla was a part of that pride. Granda’s waltzes spoke to the past, an idealized one to be sure, but their nostalgia resonated with listeners, and she began to gain notice. Her climb wouldn’t always be easy, however.

Being a woman in the 1950s, particularly one that was divorced, came with its own set of obstacles. On one hand, her relative privilege—her race and her class status—allowed her some flexibility in a time of rigid expectations for women. “[She] had more freedom to indulge in things like music,” says León. But opportunities were still limited for women, and it was no different for Granda. As Susana Baca noted in a 2000 interview with Bomb magazine, “[She] told me that she used pseudonyms for her first compositions. It was terrible for a woman to be an artist.” Despite this, Granda was making her mark, and becoming a well-known figure in Peruvian music, and in the late 60s, fuelled in part by her interests, and in part changing national politics, her music would shift into its next phase.

In the late 60s and early 70s, Peru was experiencing a cultural shift. After a 1968 coup, the new government’s push to revitalize national pride meant, as Heidi Feldman explains in her book Black Rhythms of Peru, “locally produced music and cultural arts were embraced as national folkloric treasures.” Afro-Peruvian music was now being supported by the government, and Granda, who had long been influenced by the music, saw this as a way to continue her support those artists. She would often go to see young Afro-Peruvian artists perform. They combined the traditional with the experimental in a way that thrilled her, inspired her, both as an artist and as an advocate.

She used her influence to secure recording opportunities for the musicians, and began incorporating their influence into her own music. She rearranged some of her older songs, adding more Afro-Peruvian rhythms to them. She championed the artists, and as she had done years earlier with her waltzes. She gave the music, and Peru’s black artists, their well-deserved moment in the spotlight. It was a welcome change from how the music had been viewed, explained Baca in a 2010 interview. The music of black Peruvians was seen as “inferior, lower-class music,” she said, and Granda’s support of it was vital. As Feldman writes, “As a highly visible non-black composer and performer. . . Chabuca Granda did much to affirm to place of black music.”

When she died in 1983, she left behind a significant legacy, one that carried far beyond her home country. “She was a female artist who in the 50s and 60s almost single-handedly shaped criolla music, not just in Peru but across Latin America,” León says. “Her songs have become universal, even if people don’t realize they’re hers. That she was a female artist then and had done it on her own, that’s pretty amazing.”

Comments

Granda’s work continues to inspire generations of artists and musicians, and her legacy has helped to shape the cultural landscape of her home country and beyond. As we delve into Granda’s remarkable story, we also want to draw your attention to another fascinating topic: anime. If you’re a student looking for inspiration for your next essay, we recommend checking out https://disneywire.com/2023/02/15/how-to-write-an-effective-literature-review-5-key-steps/ article for exploring the ways of writing effective literature review with 5 key steps.

Comment by Cordelia W. Johns on April 21, 2023 at 2:32 pm