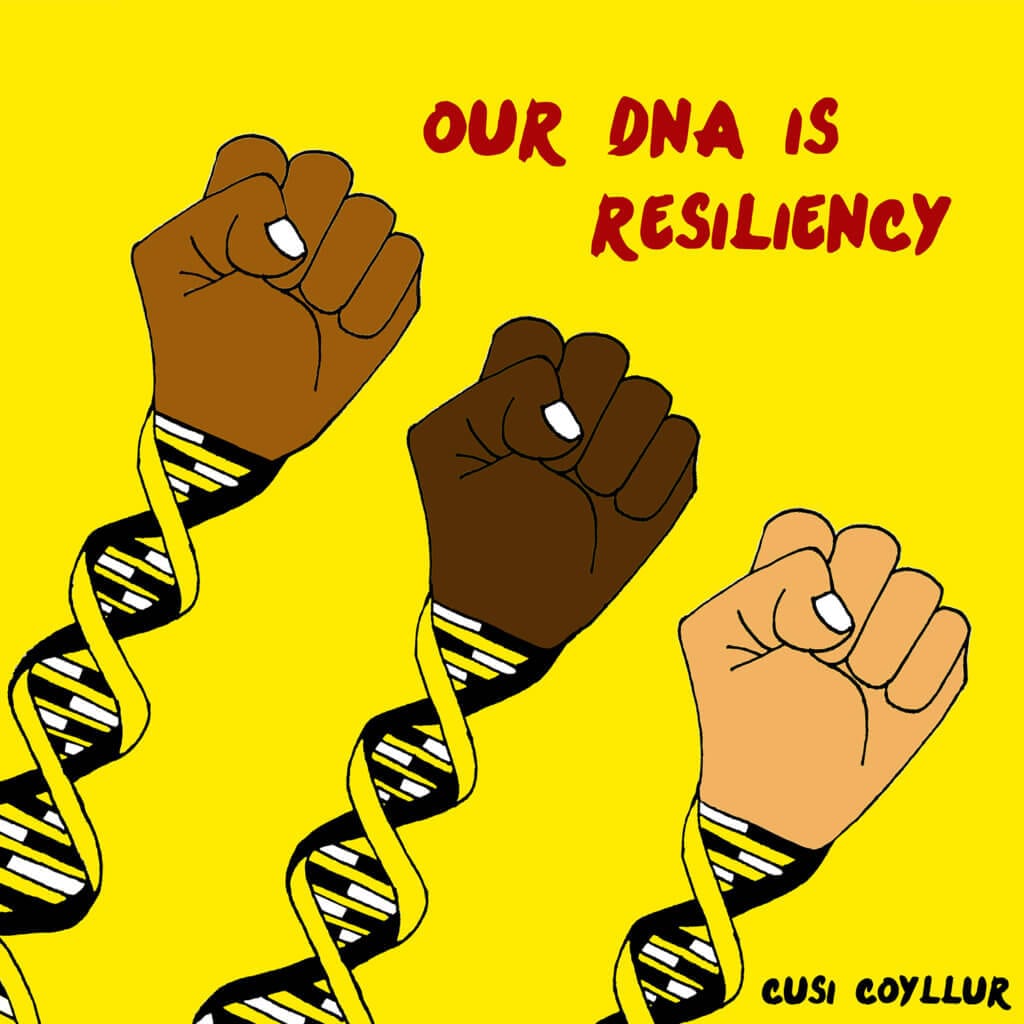

Cusi Coyllur Talks Finding Her Peruvian Roots and Resiliency in Activist Music

Shannen Roberts remembers listening to her mom’s tales of the Incas and the Spaniards when she was growing up—and one story in particular, Ollantay, has always stuck with the Peruvian-American pianist and singer. The Quechua-language play follows the titular character, an army general, as he falls in love with an Inca princess named Cusi Coyllur. Because her lover is not a part of the nobility, however, Cusi Coyllur is jailed for having an affair with Ollantay and becoming pregnant with his child. The story eventually ends with the princess’s release and marriage to her suitor, but for Roberts, the murky Spanish and Quechua origins of Ollantay are a reminder of her own mixed heritage—and so she decided to take on the name Cusi Coyllur for her musical projects.

“I say that because it is interesting that this historical, Inca story, originally told in Quechua, was not taught in my mom’s villages where Quechua is their native tongue, and was instead taught in Lima where Quechua was viewed as inferior to the Spanish language, and indigenous peoples had fewer rights and were discriminated against,” she tells She Shreds. She notes that some of the play’s content would have also been misunderstood or left out when translated to Spanish, but she ultimately sees this as a reflection of her identity.

“Like, I don’t know exactly who my ancestors are, because a lot of our history wasn’t recorded or written down, and is difficult to trace…And it’s hard to know what is true or not because since the Quechua language and indigenous peoples were so stigmatized and discriminated against, everyone wants to claim they are of ‘blue blood’ as my mom calls it, or of Spanish descent, because that is considered honorable,” she says. “So if I ask my oldest living relatives where their ancestors came from, they will say we are of Spanish royalty…and yet they speak Quechua? And live in a village? My history just doesn’t add up…yet…maybe with some more digging it will, and that’s how I felt about Cusi Coyllur’s story.”

Now based in Los Angeles, the zinemaker, experimental musician, and mental health advocate wears many hats and explores a variety of self-care and social justice themes in her work. Following the release of her single “Our DNA is Resiliency,” which raised funds for families separated at the U.S. and Mexico border, She Shreds caught up with Cusi Coyllur to discuss her musical influences, her ties to her activist community, and her use of the charango in her latest song.

Your EP “Bipolar Loves in Love” and your blog The Strange Is Beautiful both shine a light on holistic ways to heal from mental health struggles, which you name “mind obstacles.” How has writing and composing music about your personal journey shaped your own healing process?

Writing and composing music unintentionally documented my healing journey. Most of my high school songs were about struggling with panic attacks, depression, social anxiety, etc. I wrote about those things because if I didn’t, the pain wouldn’t stop, or at least ease. So I guess how it shaped my healing process was at the time, it provided a way to express the struggles I was going through, and now just by acting as an audio history of my mind obstacles. I can see how far I’ve come by listening to past songs, or remember that I’ve felt similarly before and got through it too. Clearly I’m a history fanatic, and remembering my own mental health history helps me continue to heal.

What sounds and genres influence your own style?

For “Our DNA is Resiliency”, I was inspired by Sister Mantos, Y La Bamba’s song “Mujeres,” and Pastorita Huaracina’s “Mujer Andina.” Pastorita Huaracina greatly inspired this song because she is from the same region, Ancash, that my mom and her family are from, so they listened to her A LOT. Her dad especially was a huge fan of her work and her activism to defend Quechua and indigenous peoples – such a fan that when he had a stroke and didn’t remember much, when I played him “Mujer Andina,” he sang a long. I’ve loved her since I can remember. I wanted her spirit to be in this song to fight for today’s issues – for of color families and children who were separated and caged, who have been constantly separated and abused throughout America’s history – that aren’t so different to the ones she was fighting for back then.

A lot of sounds and genres besides those ones inspire my other music though, like Sleater-Kinney, Bikini Kill, The Distillers, Bjork, Lido Pimienta, Erykah Badu, Radiohead, Kneebody, Brad Mehldau, McCoy Tyner, Chopin, Cocorosie, The Dresden Dolls, and Fiona Apple.

You’re really involved in your community and play a lot of benefit shows that promote the work of women and people of color. Why is it important for you as a creative to bridge the gap between art and activism?

I honestly have felt really depressed about playing music lately. I’ve gone through phases like this for maybe four years now where I don’t listen to music, and have no desire to play music. The one thing that will get me to play music is when I feel like I NEED to say something, and it’s usually about a mental health or social justice issue. Same with performing, which is why I love to play benefit shows. It just feels right to play for a cause that I believe in, to use my art to help others, versus playing just to play.

There’s a Kathleen Hanna documentary called “The Punk Singer” where they show a clip of Hanna talking about how she started out as a poet, but felt like people still weren’t caring about the things she was saying. So someone told her that she should be in a band because people listen to you if you sing about it. That really impacted me because I feel that issues of mental health are often things that people don’t want to hear about, especially if they themselves have never had mental health issues such as depression. Expressing activism issues through art is a way to get people to listen and to be engaged, possibly change their perspective, and maybe even inspire them to take action or change something about their lives. Something about art and music moves people, and can sometimes be more impactful than reading an article that tells them the facts and cites research studies.

Also, sometimes shows I’ve played that put womxn or people of color in the forefront are not just about activism for me, but is also an opportunity to feel safe in those spaces—to feel safe wearing a “Fuck ICE” shirt and to talk about feminist issues, or to feel a sense of loving and warm community from people of similar backgrounds as me.

Your single “Our DNA is Resiliency” addresses the separation of families at the border and features a charango. How long have you been playing for?

I’ve never played the charango consistently, or taken lessons, or anything like that. I have, however, listened to huaynos since I was out of the womb. Huaynos are a type of traditional Andean music of Peru, and they are the music my mom grew up with in the village. I was obsessed with everything to do with Peruvian culture since I can remember, and always wanted to listen to the traditional music, hear the stories, and learn how to cook the food. When I was about 13 years old, I went to Peru for the first time and my parents bought my brother a charango. He never played it once we came back home, so I would play it and write songs on it with my friends. Years later, my mom returned to Peru and bought me one too, and that’s the one I used to record this song.

What inspired you to incorporate it into the song?

I’ve never played the charango consistently, or taken lessons, or anything like that. I have, however, listened to huaynos since I was out of the womb. Huaynos are a type of traditional Andean music of Peru, and they are the music my mom grew up with in the village. I was obsessed with everything to do with Peruvian culture since I can remember, and always wanted to listen to the traditional music, hear the stories, and learn how to cook the food. When I was about 13 years old, I went to Peru for the first time and my parents bought my brother a charango. He never played it once we came back home, so I would play it and write songs on it with my friends. Years later, my mom returned to Peru and bought me one too, and that’s the one I used to record this song.

What inspired you to incorporate it into the song?

I always wanted to incorporate the traditional Peruvian sounds I grew up listening to into my music, but hadn’t found a song that it felt right for it yet. Supposedly (and I say supposedly because it is hard to know what is true on the internet), Pastorita Huaracina once said that to wear traditional Andean clothes, you must wear it with honor and with a consciousness of the people you’re representing. That’s how I feel about the charango, pan pipes, and Peruvian percussion that I wanted to include in my music for so long. I had to make sure that when I did include it, it honored the tradition and people of the Andes, and yet different enough to not be ripping off a huayno and to show my own personal creativity. I knew this song needed charango because of the topic. I wanted to create an anthem to empower people of color that though we all have inherited trauma, we are still here, and still fighting— we’ve survived through all attempts to extinguish us—so that means we’ve also inherited resilience.

Comments

Life is full of surprises and we are not always waiting for good moments and pleasant surprises. Help with mental and psychological health online is very relevant now. I think people need it. The main thing is to find a reliable resource.

Comment by Sara on April 17, 2023 at 1:24 pmI love listening to songs in English but I rarely understand what is being sung about. Therefore, I recently decided to study English and found this site https://promova.com/tutors/english-writing-tutor with the opportunity to get the services of a tutor. Now I study with this tutor twice a week and devote the rest of the time to improving my vocabulary in English and it gives good results.

Comment by Kerry Smith on August 16, 2023 at 11:50 pm