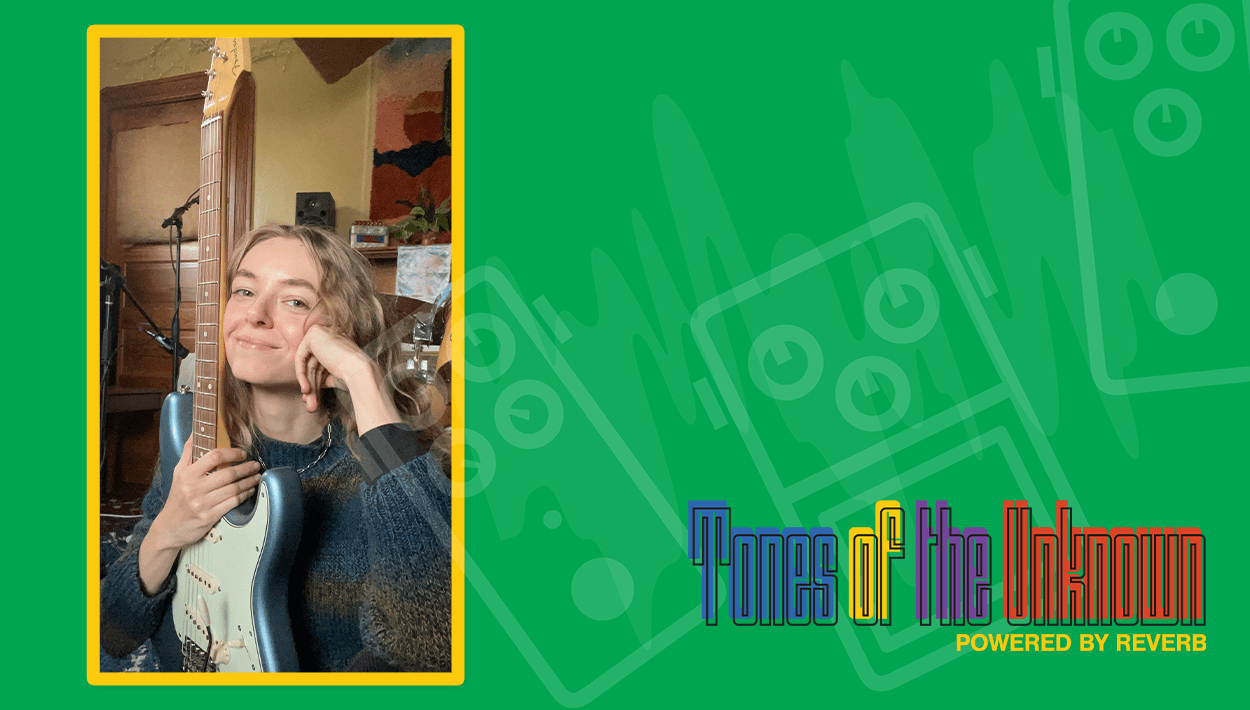

Hurray for the Riff Raff’s Alynda Segarra Activates Change Through Visibility with The Navigator

This feature originally appeared in the twelfth issue of She Shreds, published in April, 2017.

Alynda Segarra, visionary in Hurray for the Riff Raff, finds inspiration in movement. Born and raised in the Bronx, Segarra made her first move train hopping to New Orleans, Louisiana when she was 17 years old.

Since then, she’s traveled back and forth between Nashville and New York, but most recently has settled down in Harlem. This constant movement is in her Puerto Rican blood, and it translates into her necessity to write and perform music, and to connect with her roots in a culture that can be defined through dance, struggle, protest, and value of community.

While Segarra has always possessed a gift for bringing people together through story, she grapples with the juxtaposition of being a queer, Latina woman sharing experiences in the predominantly white genre of Americana. But the lack of visibility is also strengthening, inspiring her to use her musical influence to activate change. The Navigator, Segarra’s second release on ATO Records, released on March 10th, is a compelling view into this balancing of suppression and reinvention, told through a fictitious narrator who resembles herself. “When I woke up it was all gone, they took it when I was asleep,” Segarra sings in the song “Fourteen Floors,” eloquently speaking to an experience of the modern American dilemma. The Navigator is one of the best musical documentations of the experiences we go through as immigrants, people of color, and marginalized communities today. For this reason, we were thrilled to get a chance to talk with Segarra about her relationship with music versus activism, and assimilation versus acclimation in today’s cultural climate.

She Shreds: What was your relationship with music like as a kid, and how did it develop growing up?

Alynda Segarra: I always wanted to be a musician. When I was little, I would play music with my dad. I would sing and he would play piano. My dad’s a great musician. He was actually a music teacher for many years. We would play “Somewhere Over The Rainbow,” show tunes and that kind of stuff. And then I just got so deep into music and lyrics around middle school. l started playing guitar, learning Nirvana and Hole songs. But then I just got so insecure, and kind of went inward and gave it up. I thought I wasn’t good enough. It took me until I was 17 or 18 to really pick it up again, and then it was really sort of a necessity. When I started traveling, I really needed to make money, and playing music on the street was a great way, and a great way to make friends. In New Orleans I met some kids that were just totally down to play music with me, and help me learn. I got really lucky with finding a supportive group. Also, it was really equal gender-wise. It felt like such a good way to learn, and to learn how to believe in myself. Lyrics always meant so much to me and I was always deeply listening to them.

Do you remember the first song that really changed you?

Definitely some Ani DiFranco when I was in middle school. I learned the lyrics to “Fixing Her Hair” and tried to learn it on guitar. I remember being so struck by that whole story, and also by the feminist statement of it. She’s talking about being there with her best friend [who] is doing her hair in the mirror and talking about this guy that she’s with, and Ani knows that the man is really abusive to her, and doesn’t treat her the way she deserves. The whole story really spoke to me. Music like that really took me when I was 13, 14. Just feeling like I didn’t belong anywhere, and also starting to question everything around me, like, “I kind of think this is bullshit.”

As a kid, I listened to so much punk and rock, but I didn’t notice until recently that most of it was by white people. Do you feel like that influenced you—despite them being great spaces—and added to your insecurity growing up, being a woman of color and not being able to see yourself in the people and the bands you loved?

Yeah, and it really made me feel like Puerto Rican people had not contributed anything. My father was always playing Latin jazz. He was very vocal about how our culture is really rich and fucking awesome. But what I was interested in, I had this feeling of like, “Puerto Rican people aren’t conscious, and they aren’t rebels.” I just had these imposed views that Puerto Rican people and people of color should not add to what I was interested in, which was rebellious music, protest music, and stuff like that. That’s fucking crazy to think about! How did I get convinced [of] that, you know? When I was little, I totally wanted to be white. Now I look back and that is so wild, because I’m already kind of fair-skinned. And the idea of me doing that when I was a little kid just breaks my heart. I really wanted to separate myself from my family and culture. A lot of this album was about making that all right for me. Navi, the character that I channel, is me being like, “Navi, you’ve got to make right with your people. You don’t love your people like you should. You’re going to realize how lucky you are to come from Puerto Rican people, and how unique and beautiful and heavy that culture is, and how rebellious and poetic it is.” It’s me really wanting to put some energy out there for younger Latin kids, queer Latin kids, Latin women. Just being like, “You come from a lineage of fucking fighters and really incredible artists.” It was a really emotional, spiritual experience to make it.

In recent years, what has made you realize that this is something you need to not just learn more about, but also speak about?

It definitely had to do with leaving New Orleans and going to Nashville. [That] was the first time I truly experienced culture shock. I definitely felt like I didn’t belong there. I was like, “Damn, I’m really not around my people.” Also, I went to a feminist conference in Puerto Rico that just fucking changed my life. Angela Davis, bell hooks, and a lot of really amazing Puerto Rican feminist activists spoke there. Just to be there, on the land, experiencing this. I felt like I needed to do right by this feeling and start really understanding it. Watching the news, I’m like, “Wow, I was so in the dark about how in danger black people are every day in our fucking country,” and feeling very deeply affected by it. And then I see a lot of people who don’t seem to be affected by this. Why is that? Just really finally being like, “I’m a fucking person of color,” and these are my issues. I feel very attached to the issues of other people of color, and I feel like my freedom has depended on their freedom. I have privilege, but I feel like their struggles are struggles I want to fight for. Of course, with the new administration, and the fucking propaganda that’s getting pushed out about border issues once again, I feel like these are my issues. It started to become a feeling more of this intersectional struggle. It’s time for me to just really own who I am.

As musicians, we have a specific kind of role in this whole fight. What do you feel your role is?

What I feel is right for me is to go out and really try to make people feel like they’re not alone, and be there for people who feel like they’re very scared, and to just really try to keep that form of sanity happening. I feel like we’re really using a lot of gravity right now. The whole past couple of months, it’s like, “Wow, people can get elected not being held accountable for their actions at all!” We kind of knew that, but now it’s really glaring. It feels a lot like the veils are being lifted. I would love to be a musician out there making music who is like, “Hey there everybody! We need to remember what our values are as human beings!” I would love to bring it down to basics, because the way we are going is so dark. We need to be envisioning a future that is peaceful and full of basic human rights. I think a lot about manifesting and envisioning futures, because if you don’t see our future, somebody else will make it for us. We have power as people.

Do you feel like a lot of musicians are feeling that way now as well? Is that a community outlook in the music industry? Or does it need to be pushed more?

It could always be pushed more. There is an idea that musicians are entertainers—[so] we’re not supposed to have opinions about the way our world is formed? That’s propaganda to try to shut us up. I feel like the music industry is pushing for people to be vocal. Solange’s A Seat At The Table—I was like, “This is revolutionary music!” People are really putting out amazing stuff right now. We see it with Meryl Streep, and we see it with these big time entertainers. I think artists are really going to play a big role. It’s not illegal to criticize our elected officials! That’s normal! We need somebody to say it or else we’ll just be bullied into that being true.

I’ve read previous interviews where you talk about how first generation Latin Americans have to assimilate. I wonder if you’ve had to assimilate in order to be taken seriously as an artist, in your genre, who’s openly queer and also Latina?

I was really lucky. I came into music in such a DIY punk way. From the very beginning, I was like, this is who I am. I was not that open or in touch with being Puerto Rican, so I wasn’t talking about that as much. But when Small Town Heroes came around, and with ATO [Records], I was like, “This is who I am, and that’s what you’re going to get,” and they’ve always been extremely supportive of me. But I definitely felt like being in the Americana scene made me uncomfortable. I didn’t feel a lot of tension [in regard to] my worries about the world. As I said, reading things about Trayvon Martin and Mike Brown and Eric Garner, the list goes on, I was like, “Wow, is this not bothering anyone else?” So, I always did my best to stay vocal. Most of all, I wanted my audience to be aware, because if they weren’t down for that, I wanted to let them know that they could not come to the shows. If that is not what you are about, that is totally fine, but I’m not going to stop being me for you. I’ve always tried to be open about my beliefs for my audience,.

Within the Americana genre and the music industry, what does the term “woman of color” mean to you, in comparison to how the world of music sees it?

I have an interesting relationship with it in the industry, because I feel like I have so much privilege. There are a lot of people who are comfortable with me being so outspoken because they kind of see me as a white girl. I get away with saying shit that people who are darker skinned than me would not get away with. I am very aware of it, and there’s a part of me that wants to talk louder because I’m getting away with it. If you’re going to listen to me, I’m going to tell you that all the shit that’s going on is fucked up. So it’s interesting, because I feel like I have this privilege, no doubt, and I’m aware of it.

What are some of the main things you love and want to know more about in Puerto Rico?

I have a book I just got about this poet Julia de Burgos, who I’ve always heard about, but I’m falling more in love with her all the time. She’s this feminist poet from the fucking ’30s and ‘40s. And I’m really getting into the history of bomba and plena music, the folk music of Puerto Rico. Most of all, though, I want to get in touch with the activists on the island to amplify their work.

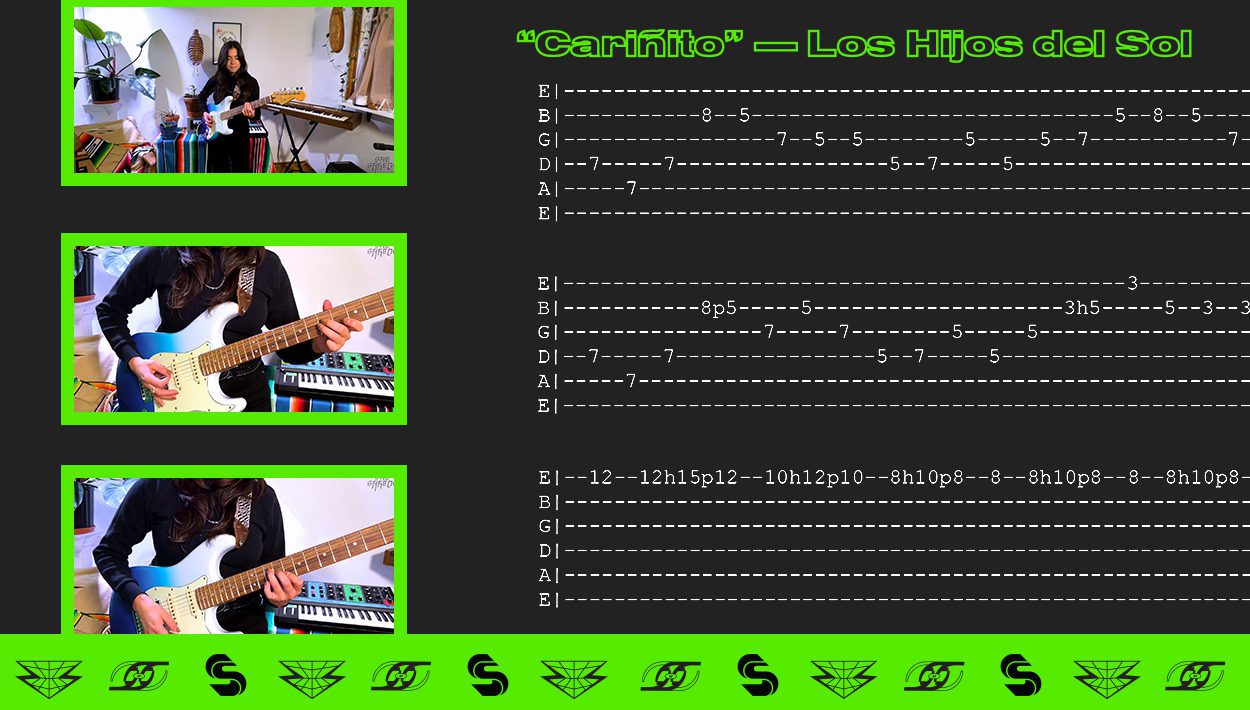

The rhythms of Latin America are so vast and deep and amazing. Talking more about your guitar playing, would you consider yourself a rhythm guitar player?`

I see myself as a rhythm guitarist, but I also love finger picking. It reminds me of playing banjo, and what I love is rhythm in general. I find it really meditative. It’s what I first loved about music because I felt not as intimidated by it. I felt like I could just feel it, as opposed to having to figure out the math of it. So, that’s what I’m drawn to. I love being really simple. It’s so important.

Within a band, what kind of space do you feel like that type of guitar playing fills?

I want to be the rhythm because I like to make things fall in certain ways. I play the part on “Settle” where I just really dig into certain beats. I just love it being me and the drummer, just laying it down, being something that people can depend on, but also need to pay attention to. I love being creative with it, but also reliable.

What do you look for in a guitar?

A good bass. Definitely. I have this 1968 Gibson that I just love. You play a G chord and you’re like, “That sounds like a band.” It’s so rich and the bass is so deep. My first one was an archtop Harmony that I got off Craigslist, and that was my best friend for a while—that’s what I learned on. Now I have this old Kay archtop electric that I’ve been playing, and it’s really fun because it’s kind of between an acoustic and an electric.

Lastly, in speaking more about influencing the younger generation of women who are queer and Latina or women of color who are musicians, what is something that might help with the feeling of being alone?

I think the only thing that can help is just being really vocal, you know? And just really trying to keep in touch with each other. I think that’s really it—we all have to get through and be here for each other. I need to do my best to connect with other artists who are feeling some anxieties and to take care of each other as much as possible.

Comments

[…] that night, (a solo set of songs I’d written with my twink punk band, Gloryhole), along with Alynda Lee Segarra, who still makes music under the name Hurray For The Riff Raff. I can vividly remember sitting on […]

Pingback by She Shreds Media on June 12, 2020 at 11:45 am