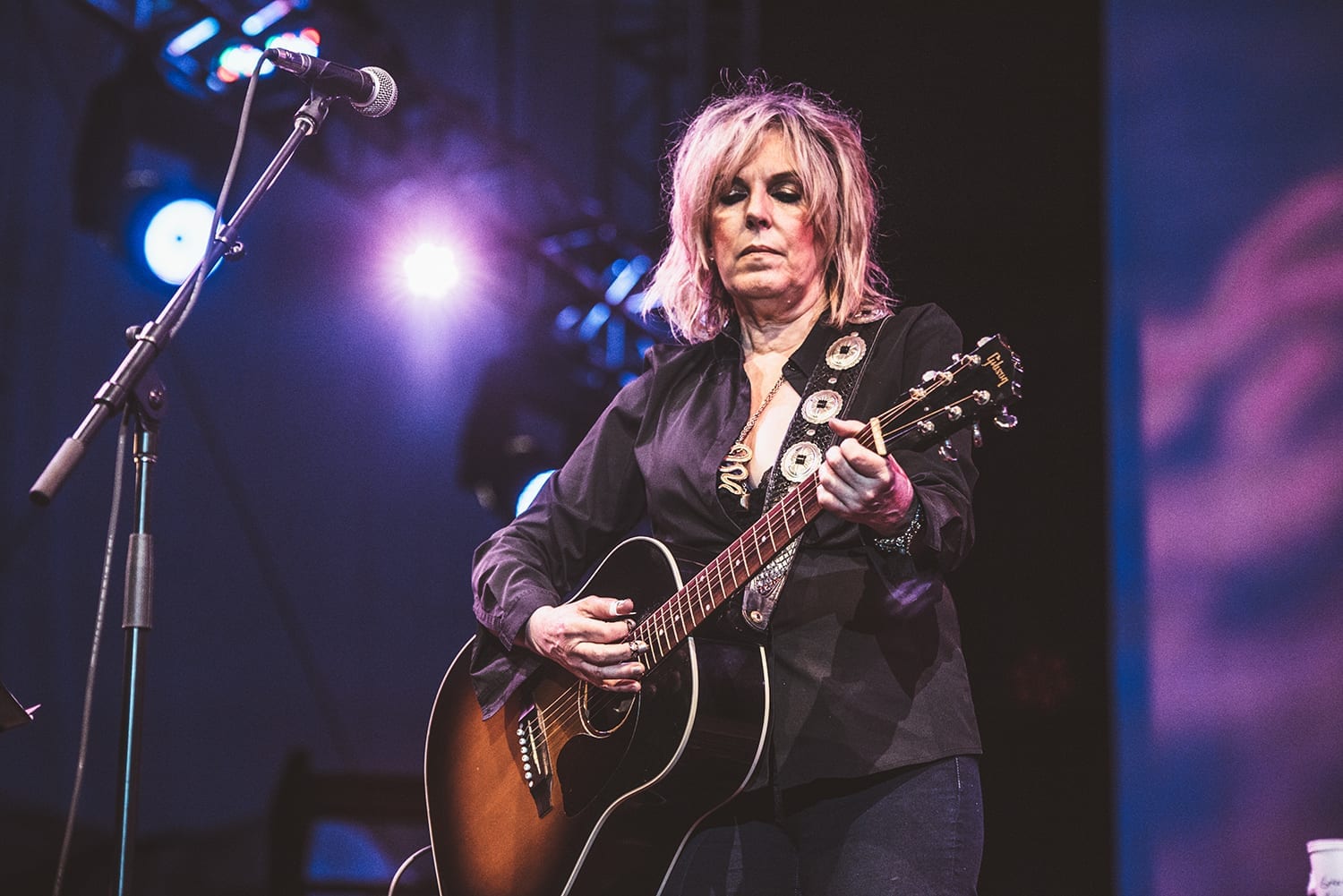

Lucinda Williams On the Hard and Sedulous Road to Major Label Success

[This feature originally appeared in the eleventh issue of She Shreds, published in November, 2016. Subscribe here and receive your copy of She Shreds’ 12th issue with your subscription.]

The roads Lucinda Williams has traveled to carve out a space for herself in the music industry have been expansive, haunting, and often unpaved.

As a Southern singer-songwriter who walked the line between rock and country before Americana formally existed, she was long evaded by major labels. Despite years of being overlooked, she’s released 13 studio albums; won three Grammy’s in country, folk, and rock; received a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011; and won Album of the Year for last year’s Down Where the Spirit Meets the Bone.

Throughout Williams’ career, her father—acclaimed poet Miller Williams, who may be best known for reading at Bill Clinton’s inauguration in ‘97—stood by her side as a huge source of support. His death from Alzheimer’s last year, 10 years after Williams lost her mother, is a keynote on her latest release The Ghosts of Highway 20. The apparitions of Williams’ past are presented through nostalgic lyrics, mournful guitars, and resilience. I spoke on the phone with Williams from her home in LA about her identity as a Southern singer-songwriter, the loss that permeates her sound, and starting her own record label after years of industry hardships.

She Shreds: When did you realize you wanted music to be your life?

Lucinda Williams: It really all come to fruition when I moved to Austin in 1974. That’s where I really started honing my craft and developing a little following—it was completely all on my own. I moved out to LA in late ‘84 and that’s when I got introduced to the whole business aspect of things, when I started attracting attention from some of the record labels. I got what they used to call a development deal with Sony Records. They gave you enough money for six months to pay your rent and live on—the idea being that you write songs and, if they like what you’ve done, then they sign you to a deal. That’s when I came up with the majority of the songs that would later end up on the Rough Trade album [Lucinda Williams]. Sony Nashville said it was too rock for country and Sony LA said it was too country for rock. So, that demo tape floated around for a couple of years, and eventually found its way into the hands of Rough Trade Records. It sounds sort of Cinderella-ish [laughs]. At that point I had been turned down by every label out there—all the majors, all the minors. It took a punk label from England to recognize what I was doing.

Why do you think it took so long for the majors to acknowledge your music?

The main thing was, this was all happening before the big Americana movement came about, and that market was created for the kind of music I was doing. Up until then, they just didn’t know what to do with me. It was a timing thing. There had been women singer-songwriters in the ‘70s who were successful, like Joni Mitchell and Carole King. I got caught in between that period, and at some point in the late ‘80s/early ‘90s there was that wave of female singer-songwriters, like Mary Chapin Carpenter and Tracy Chapman. I was able to catch that wave. I kept saying, “Look, we’ve all been around for all this time. There’s more where I came from.” [Laughs.] There are more of us out there.

Absolutely. That feeling of being recognized in such a grandiose way, just because you’re a woman—as if we haven’t been out there, playing and just as capable as men, this entire time.

I know—they treat it like it’s a big phenomena. It would be like, “all-girl band” or “girl drummer” and I’d be like, “Why can’t you just say drummer?” Female this, female that. It’s an oddity. [Laughs.] Well, I don’t think oddity is the right word. It’s not like we’re circus freaks or something—”Hey everybody, come look at the oddity over here! Look, it’s a woman who can actually write really good songs and sing and play guitar!”

Speaking of identity, I’m curious how your roots in the South have influenced your songwriting.

I grew up being aware that I was Southern, and that being a very important thing for me. And being drawn to short story writers, like Flannery O’Connor and Eudora Welty—the surroundings in their stories were so familiar to me, the whole Southern Gothic thing. That world only existed in that part of the country. It’s going to inform the personality of the songs. In a lot of my songwriting, I mention towns and places. It’s a culturally traditional thing in the South to tell stories. My dad was very much aware of that fact that he was Southern, and made that distinction a lot when I was growing up. Because, at the time, when he was trying to be successful as a poet, he was considered a Southern poet, much like how I was later considered a female singer-songwriter.

You lived all over the South in your youth, and you tell the stories of those places so vividly. Do you feel that the song “Ghosts of Highway 20” was a modern follow-up to the younger perspective of “Car Wheels on a Gravel Road”?

It wasn’t a conscious effort. I was talking about a lot of the same things, only now I’m older. With “Car Wheel” I was a child in the back seat—and in “Ghosts of Highway 20” I’m driving the car, looking out the window, and looking back. It’s a similar song, but coming from the perspective of the woman grown and looking at the loss. Highway 20 runs through some of the towns I grew up in, and it runs through the town of Monroe, Louisiana, where my mother was from and where she is now buried in her family plot—where she didn’t want to be buried, but that’s a whole other story. Talk about Southern Gothic. [Laughs].

Grief has always been a huge theme in your songs, but it seems particularly heavy on Ghosts of Highway 20. I know you lost your father last year—how do you feel this grief has affected your songwriting?

My mother passed away in 2004, and then my dad 10 years later. That period in between, I wrote songs like “Death Came”, and then after my father passed away I wrote, “If There’s A Heaven” and “If My Love Could Kill”, which I wrote about the Alzheimer’s disease that killed my father. There’s a lot of dealing with loss, and heavy stuff, and life. It’s a lot different of an album than some of my earlier one’s, like Essence, when I was still struggling with unrequited love as a younger girl. Now I’m a woman of 63-years-of-age and I’m having to deal with…well, I’ve always dealt with dark stuff. I mean, we deal with it from the time we’re born. We start suffering as soon as we pop out into the world. We start out crying, you know? [Laughs.] And it goes from there. I choose to write about it because it helps me deal with it. It’s very cathartic.

I’m curious to know what your process is when writing songs.

I always have a notebook and pen with me—there’s never a lack of inspiration, that’s for sure. My thing is more, when the muse strikes. And I use a Zoom, that little thing you can record into. In fact, I had this dream, and I wrote this new song in the dream, and I usually don’t remember them. And so I woke up and I said to Tom [husband and manager], “I have to put something down right now. Find the Zoom, make sure it has batteries in it.” [Laughs.] I didn’t want to forget. It’s strange how the subconscious works.

When Lost Highway folded, the label you released under for 10 years, you started Highway 20. What was the motivation to run your own label?

When Lost Highway ended, we started shopping around for a new label, and there were just some prerequisites that we wanted understood by whoever we were going to work with. We’ve cut out the middleman, so to speak. Financially, for me, it’s much more rewarding. If you own your own label, you’re not turning the profits over to a major label corporation. You know, I started on an indie label, Rough Trade, and I signed to a major label right after that, and it fell apart. So now I’m on my own label, and there are no rules. If we want to make a double album, we can. If we want to write a song that’s 19-minutes long, we can. It’s the liberty and freedom.

Comments

[…] Gospel, a country-inflected alt-rock bop dripping with a syrupy sexuality, like Sade singing a Lucinda Williams song. “When I was studying feminist theory and women’s writing, one of the things we […]

Pingback by She Shreds Media on May 5, 2020 at 10:33 am[…] like two of her idols, Lucinda Williams and Lydia Lunch, LG refuses to settle. “They never compromised,” she says. “They […]

Pingback by She Shreds Media on June 12, 2020 at 12:01 pmThe other day I was writing an essay on assignment from the university about good and bad people. It is actually a discussion question and there is even a concept that it is so difficult to meet a good person. I have even found whole essays about it from writers and scientists, you can also read https://studydriver.com/a-good-man-is-hard-to-find-essay/ go to this web-site , it seems to me that in our cold cruel world it is more relevant than ever and there is very little knowledge and information about it now. It is good that at least I managed to understand something and learn for myself.

Comment by Mitra Surik on October 29, 2020 at 8:24 amThe other day I was writing an essay on assignment from the university about good and bad people. It is actually a discussion question and there is even a concept that it is so difficult to meet a good person. I have even found whole essays about it from writers and scientists, you can also read go to this web-site , it seems to me that in our cold cruel world it is more relevant than ever and there is very little knowledge and information about it now. It is good that at least I managed to understand something and learn for myself.

Comment by https://studydriver.com/a-good-man-is-hard-to-find-essay/ on October 29, 2020 at 8:24 am[…] played Third Man in the summer of 2017. One of Cruchfield’s most beloved covers to play live, Lucinda Williams’s “Greenville,” had never been recorded prior to her set at Third Man. “To have my […]

Pingback by She Shreds Media on February 16, 2021 at 6:14 am