Shannon Wright on Finding Connection and Making Music for Music’s Sake

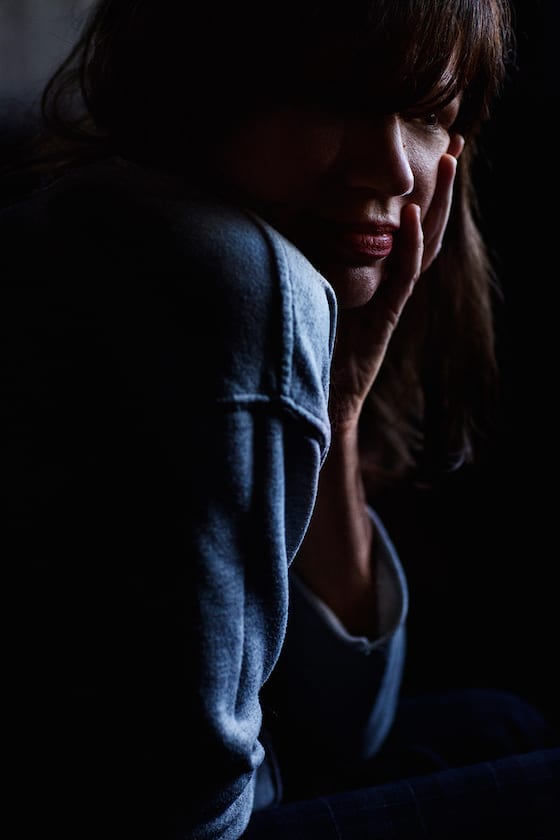

She’s been called angry, aggressive, an artist who “enjoys making people cry.” Shannon Wright has heard it all when it comes to her music, and it leaves her unfazed.

They’re words, not a reflection of who she is as a singer, songwriter, or musician. What’s important is how her work connects with those who experience it. That connection and that need to create are what drive her each time she steps onto a stage or into a studio, as she recently did to record Division.

Arriving on February 3, Division is Wright’s eleventh album. “I write a record when the record is ready to come out,” she says. “I don’t really make money off of doing this. It’s a creative passion that I adore, so I don’t force things. I don’t even think about it. I could write a record in six months. Who’s to say? It depends on when it’s ready.”

Division was recorded by French producer, composer, engineer, and musician David Chalmin, whose classical music background merged with Wright’s punk aesthetic to create what she calls “a nice combination of those two worlds colliding.” They spent a week cutting basic tracks in Rome at pianists’ Katia and Marielle Labeque’s Studio KML, which Chalmin manages, and another week at his Studio K in Paris. Wright completed the keyboard parts at home in Atlanta.

Wright describes the album as more experimental, with its use of electronic drums, in addition to acoustic drums played by Raphael Seguinier, and more piano-oriented, with classical stylings, in contrast to her previous guitar-heavy projects.

“I don’t choose what style of record I’m going to make,” she says. “It comes out as it comes out. The actual notes, however they come together, are the vehicle for the mood of the song. Rarely have I written lyrics first. I might write down some ideas, and on occasion a song will come out all at once from start to finish. That’s happened a few times. I just let things guide themselves, and this is what happened. Once I allowed myself to get inside of it, it was a lot of fun. I enjoyed it. I’m really happy with the outcome.”

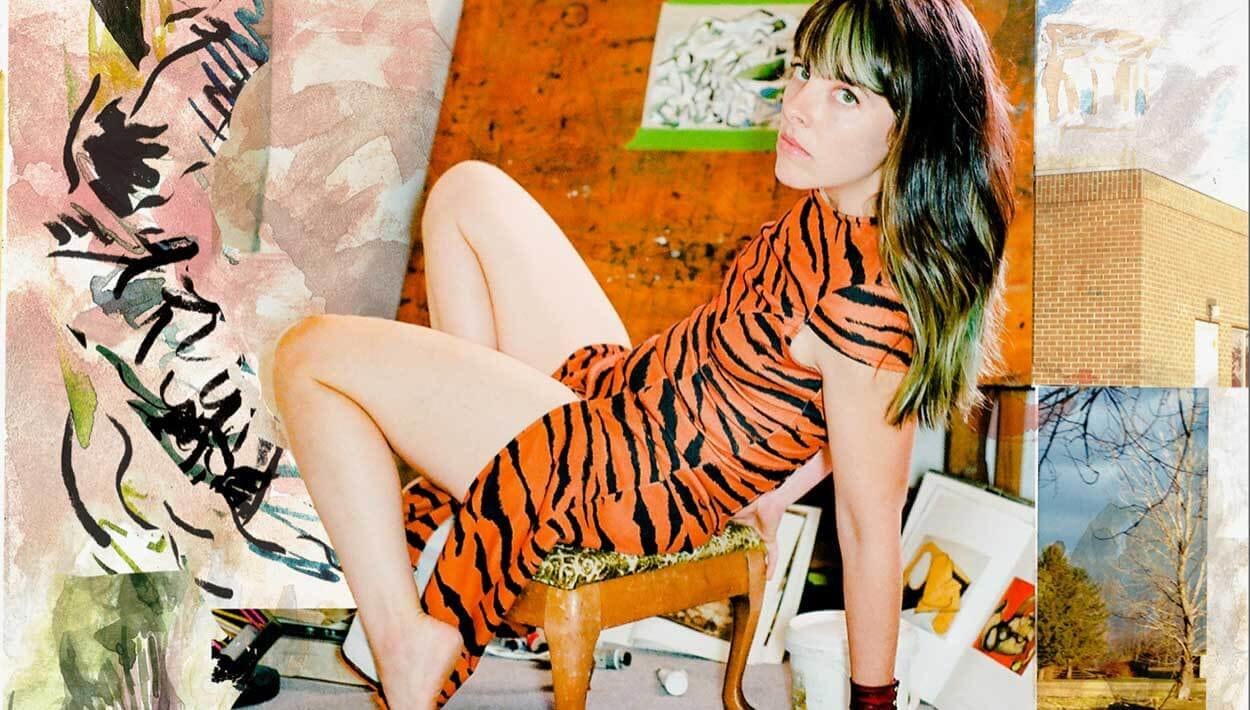

Wright was born in Florida and became enamored with music at a young age. She gravitated toward punk rock, but developed a solid background that encompassed a number of genres that can be heard in her music, which is equal parts aggression and tenderness. Once she learned to play guitar, there was no turning back. Her career trajectory took her from Florida to New York with her band, Crowsdell, to North Carolina, where she began her solo career, and finally to Atlanta, where she resides.

In 1998, she signed with Chicago-based independent label Touch & Go Records, best known for its roster of underground, punk, and hardcore bands, among them Butthole Surfers, The Jesus Lizard, Shellac, and Yeah Yeah Yeahs. She released her debut album, Flightsafety, the following year. Between that album and Division, she recorded nine other albums, including Maps of Tacit (2000), Dyed In The Wool (2001) and Over The Sun (2004), all of which paired her with recording engineer and Shellac guitarist/vocalist Steve Albini. During the decade she spent signed to Touch and Go, Wright toured relentlessly, trying to make a name for herself in the U.S. to little avail. European audiences, however, quickly embraced her raw lyrics and intimate performances. Seizing the opportunity, Wright refocused her career, signing with French record label Vicious Circle. These days, majority of her personal and professional time is spent in Europe.

She Shreds recent spoke with Wright from her home in Atlanta. A condensed version of our conversation follows. Division will be available through Vicious Circle on February 3.

She Shreds: You mentioned that you “write a record when the record is ready to come out.” When did you begin working on the songs that became Division?

Shannon Wright: I meant that I don’t force songs out of me like it’s an obligation. After meeting Katia Labeque, she offered me her studio to just take time and see if I wanted to start writing with no pressure—purely for inspiration. I wrote two songs the second day of being there and the rest just followed. We recorded the basic tracks the following day and thus began the process. I went back home and started writing more songs and it all fell into place.

What is the theme or connecting thread on Division that brings all of the songs together?

There is no theme. Maybe they’re threaded in the way one might write a short story or book of poems. Each piece is linked together only to exist for the other.

How did you develop your career in Europe?

I was on tour with Calexico. I was playing a show in Paris, opening for them, and a guy who ran an independent record label was there. He was on his way out of the club and he heard my music. He said it stopped him in his shoes, so he ran back and he was like, “How do I meet this woman?” He was supposed to leave, but he stayed and we met. He was very excited. I thought he was genuine and kind and enthusiastic, and I was struck by him. I was already on Southern, which is what Touch and Go went through [for distribution] in Europe, but it didn’t work well between us. I don’t think they knew what to do with a solo artist, and my music wasn’t really punk rock, so they weren’t finding a place for me. I felt like this guy at least was excited, and that was more important to me than somebody’s name or whatever. It turned out well, and we’ve been super-close friends since then. It was a sort of destiny meeting, I think.

It all started from there. I would go on tour over there and the audiences really identified with my music, much more than anywhere else. I think it’s because it’s emotive music. It pulls up feelings inside of you that maybe you don’t always confront. Especially in France, people are very emotive. They want to feel things; that’s what life is about for them, and so somehow it intertwines. They recognize themselves in the music, even though it’s sung in English.

In recent years you have maintained a lower profile in the U.S. than in Europe. Why?

I tour in Europe much more than I do here. Only recently have I been touring here, and it’s because of my friends in Shellac. As far as living, depending on how much I’m touring per year, I spend sometimes half a year over there. It wasn’t deliberate. I was on Touch and Go for ten years and it didn’t happen for me. I think I was just too…people thought I was angry, they thought I was too abrasive, whatever. It didn’t work. To me, it was, “Why can the Jesus Lizard can be abrasive and crazy and I can’t be? Because I’m female? Or because — what is it?” In Europe, people were like, “Oh yes, we want this,” so I went where the people were like me, who didn’t think about the fact that I was female.

I think over here it’s slowly changed, but when I was on Touch and Go, that was something they could never understand — why I toured like crazy in the States and I just never worked. I did it for ten years straight, 200 days out of the year, and I couldn’t do it any more. People didn’t get it, which is fine, but it was pretty exhausting. It was hard work. I was more of a musician’s musician as well. I had several big-name bands take me on tour because they liked the music, but the crowds were always a battle, so once I discovered that in Europe people understood me, I didn’t see the point in continuing tour after tour. The irony now is if I go on tour with Shellac, the audience is so receptive, and it’s kind of “too little, too late” in a way for me.

What should American musicians looking to expand into, or focus on, Europe know about that market?

The main thing is to stay true to yourself. It’s very different over there. Also, you have to be respectful of other cultures; otherwise, people won’t be as open to you. If you’re sincere, people see that and you have a chance. But I don’t have any advice as far as how to make it happen.

How was the music you made with your band and early in your solo career related to what you do now? Is that what brought you to this place as a singer and songwriter?

I don’t think it’s really brought me anywhere. It’s just my life. Life is so erratic and crazy; there’s not like picking up sticks and grabbing them and making a big pile at the end, I don’t think. At least, my life’s not like that. It’s burning one stick at a time. That’s what I’m doing, and I don’t know what came before or what’s coming after. I don’t know how to not do music. That’s been the one thread through my entire life since I started doing it. I can’t live without it, I don’t know how to live without it, so I keep making records because that’s what feels natural. What’s unnatural is when I’m not doing it. So when people ask me, “How did you decide to do this record?” I don’t really understand it myself. I don’t know. There’s no definitive answer. It’s just what it is, its own sort of beast, and that can be super joyful and painful all in one.

You tried to step away from it a few times.

Yes, I did. It’s not an easy life. There’s a part of me that would like it to be easier, but I can’t not do it. I fall apart when I don’t do it. And I enjoy the connection with other people. I think it’s important. I think art is very important for everybody. It’s essential. You get to a certain age and society thinks you’re supposed to quit doing music. Music is very ageist. An artist’s life can be difficult. It doesn’t make sense to the majority of people. The ones who are in the music industry, whether they write about music or work for a record label, understand how it is, but outside of that, most people don’t understand. It can seep into the artist’s life in a way that can make you feel like an outsider, and that you’re not living a certain way you should be living, so sometimes it can be difficult. But it’s not the hardest thing in the world. It’s actually not a big deal, but it can bring you down at times. And there’s not a lot of money in it, if you’re truly doing it for the art. I never looked to be a rock star. That never happened for me, and it wasn’t something I ever sought out. I always wanted to be the best songwriter I could possibly be and the best guitar player I could possibly be. Those were my goals.

Have all of those experiences influenced your songwriting and worldview?

I think so, a little bit. I don’t understand why, but since I was a kid I always felt out of place in general, and that alone will make you look at life differently. As far as culturally, I think American culture is a bubble, and it can be ridiculous when you step outside of it and look back at it. It’s really crazy and it can even be disturbing, but when you’re living in it, you don’t know the difference. Going to Europe as often as I do, I see things through other people’s eyes, and I also see it through other media, whether it be France or Italy or Belgium or Switzerland. I see everybody’s take on it. Also, because I’m American, they have preconceptions of the way they think I am and will behave when they meet me. It’s an interesting thing and it can be pretty heavy sometimes.

You are not shy about ripping open your emotions in your songs. It sounds contradictory, but does it take a thick skin to be that vulnerable?

Definitely, but there’s a lot of freedom in letting yourself be vulnerable. It takes a lot of work to protect yourself. It takes a lot of work to cover up all your emotions and all your stories and pretend you’re somebody else. If you’re just you, then you’re free, and that freedom has kept me happy. If somebody comes to my show and they don’t like it, I am more than happy to give them their money back and have them leave, rather than try to play a show for them. I think the audience understands what I’m doing, because I like to see those types of shows too. I want to be moved. What are we here for if we can’t go somewhere, see a piece of art, and be completely touched by it, and moved by it, and be gutted by it? Not in a dark way, not in an ugly way, but in a way that makes you feel something. That’s beautiful.

A lot of people have said I’m dark, I’m this, I’m heavy, I’m angry, I’m whatever. It’s all just words. It’s not even real. The truth is when somebody comes to a show and sees the truth without being told what they should feel. They just feel it. They feel connected to me, and I feel connected to the audience. That’s important, because otherwise we all become numb beings. To lose an art form, or to lose artists, that can pull that out of us is terrible.

I don’t want to think of a society where that doesn’t happen anymore, where we’re just walking around numb. What kind of life is that? What is the point? So if I make people cry, it doesn’t mean that it’s bad. It means that we’re alike. We have the same heart, the same feelings, the same things that we need to work on, or we just need somebody to put their arm around us and say, “You’re all right.” That’s what art is. It’s an extension of us that we don’t need to speak. We don’t need to sit down and have a conversation about it. It just is. And to me, that is beautiful.

Comments

No comments yet