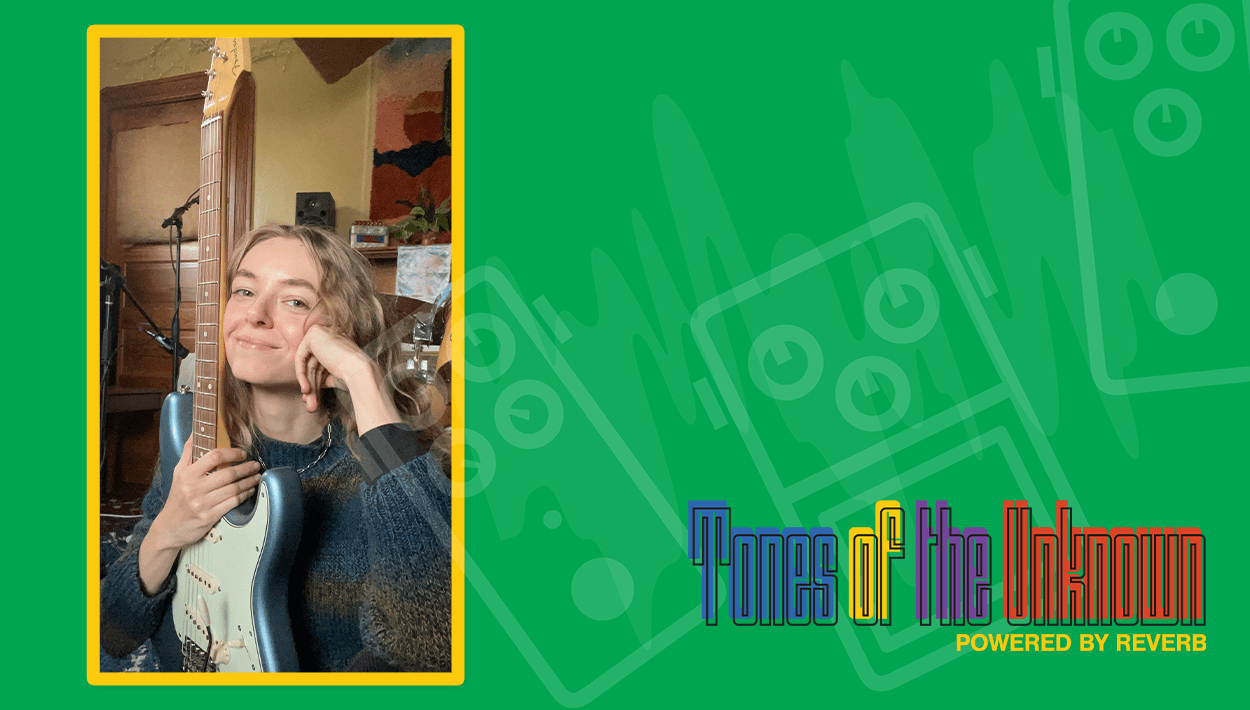

Kate Rhudy and her Southern Community

From working under a DIY ethos to using humor in her work, Kate Rhudy is changing the name of country by doing things her own way.

Kate Rhudy loves the service industry: “Even if I’m a musician full time, I hope that I can always pick up shifts at a restaurant someday. I still kind of hope that I’m able to be at home.” Back in her hometown of Raleigh, North Carolina, Rhudy wears a worn-in sweatshirt and pours fresh coffee at her kitchen table. Her home is like a sanctuary; shared with three friends, it’s lived in and warmed by sunlight.

In 2017, Rhudy self-released her debut album, Rock N’ Roll Ain’t for Me, two days before her 22nd birthday. Tracing her Appalachian folk influences to the years she spent performing in fiddler’s conventions with her big sister, Rhudy commemorates her classical violin training, learning by ear, and a childhood in Raleigh immersed in acoustic music. In the hours before her daily shift at the restaurant where she works, Rhudy talks to She Shreds about feminism in the South, DIY in country music, and building your community.

Your songs hold a lot of sarcasm, but are still optimistic. What is the role of using humor in your songwriting process?

Humor is the way my brain works. It’s how I’m able to process things. It’s a way of not letting something stay a demon forever in your mind. And that’s what songs are for me—taking a bad experience, wrapping it up, putting a bow on it, and letting it be. Not being too precious about it, but being able to bundle it up and then put it aside.

A friend played me your absolute banger, “I Don’t Like You or Your Band.” I’d love to hear about your experiences with dating other musicians and navigating music egos.

I haven’t dated a boy in a band since college. And he was fine. I started really noticing the way people “in the scene” would act, and it was super frustrating. [That song] is so specific, and I wrote it to get it out of my system. But everybody knows that person. You can be that person.

I try to be as honest as I can in my songwriting. The first line, “I was in love with a good, good man”—I mean that part. It sounds sort of sarcastic when I go on to say “…And a cheater and a liar, don’t forget drunk driver,” but I try to sincerely acknowledge that I was in love with a good person, and the duality of humans. Good people do stupid things.

What is the role of your community in your music?

In the past three years, I’ve formed relationships with people who are in my band and other bands in The Triangle [Durham, Raleigh, Chapel Hill] and it’s really sweet. The best thing about my music community is it’s not my life all the time; my community is my restaurant and my roommates, and that’s really nice. That is really nourishing, that music isn’t in my face all the time. I feel lucky to have both: a good music family and immediate community.

I often associate DIY with punk or lo-fi bedroom pop music, and so I’m fascinated with what DIY country and folk looks like.

DIY is fun. You can do anything. Catching up with my best friend is like, “I want to make match books.” And she’s like, “Let’s look at all the designs, let’s do it!” Me and her are just like kids. During her day job she’ll send me edits of a music video we made; it’s just iPhone footage that we’re going to put to one of my songs. That kind of stuff keeps you engaged.

Did you want a band? What was the process in going by your name?

I figured that the only person who cared about what I was doing was me. It would be so frustrating to get people to care as much as I do. I do have a band—my friends Alex Bingham [bass] and Ryan Johnson [electric guitar]—and they’re awesome. I figured that if I focus on being a solo artist for a while, one day, when I can afford it, I’ll take them on tour.

How does Raleigh allow you to make the music that you want to make and live the life that you want?

In this new year, I’ve been trying to make sure I’ve got all the simple things down before thinking about music. It’s life first, music second. Music is a part of my day-to-day, but outside of music, my life is super simple. I work in a restaurant six days a week, I live paycheck to paycheck. It’s nice to be surrounded by people who are working hard and have dreams no matter what industry it is. And it’s really nice to be surrounded by different inspirations.

It’s a quieter, slower-moving life here. I live in a neighborhood. I can walk to work. I know the bartenders at the bar down the street, they’ll open the pool table so you can play for free.

When you’re touring, especially in New York or LA, how do you handle misconceptions people may have about the South?

I’m so in my own bubble that sometimes I don’t even realize that people are making comments about the South. But it’s either they’re making fun of it or they’re glamorizing it.

I consider myself lucky to have grown up in the spaces that I did. I grew up in a liberal Baptist church that got kicked out of the Southern Baptist Convention, and our pastor—a queer woman—leads marches and sit-ins. I grew up in a city, in a blue bubble. I’m not surrounded by things that people make fun of the South for, so it’s hard for me to even understand those criticisms—that’s not the South that I know. But also, I’m a cisgendered white woman, and I don’t encounter the everyday discomfort [that others do].

And how do you navigate being a feminist artist in the South? How does that play into your creative process?

The lens I see the world through is naturally very feminist, and I hope the music I make reflects that. That’s not to say my process couldn’t be more intentional; it’s easy to see the world through a feminist lens, to envision the world you want, but a lot of work goes into making it happen. I want to play music with more women, and that has to be something I intentionally seek out.

I frequently find myself in male-dominated spaces. But that being said, from my opinion, it seems easier for me and my women and queer friends to do our thing. The industry feels more accessible. We also have the internet, we have ways of connecting. More than ever people are lifting each other up, but for some reason, I still find myself in a room full of men all the time.

And what’s coming up for you?

I’m working on a new record now, recording with my friends, trying to figure out how to not just be adding voice to the void. That’s what I’ve been trying to figure out recently. “What am I saying?!” Once I figure out the structure of everything, I’ll have my plan in place.

Comments

Do you know your family heritage?

Comment by DeWayne Rhudy on December 12, 2019 at 6:08 amI just want to say; I’m in love with your song ‘”I don’t think you’re an angel anymore.” I just recently found this. As an old soul folk singer/songwriter, I have a real appreciation for the passion in this song. You speak in my language; not like one speaks Irish Gaelic, but more like a Voltaire who speaks reason to the enlightened.

Comment by Christian on March 14, 2022 at 2:09 am