The Big Sky Love of Sachiko Kanenobu

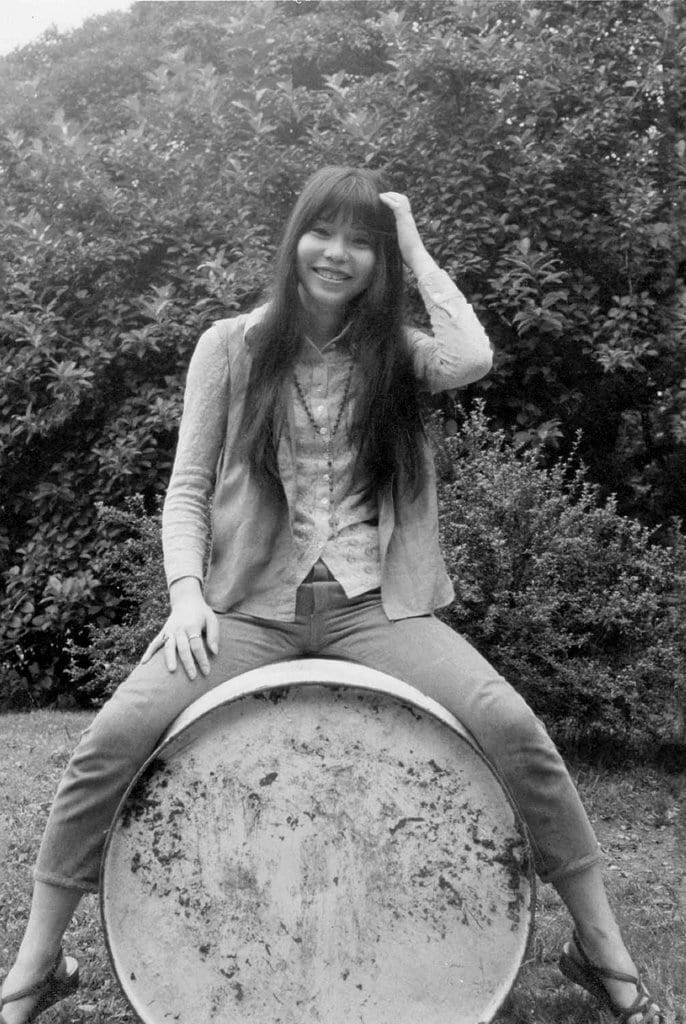

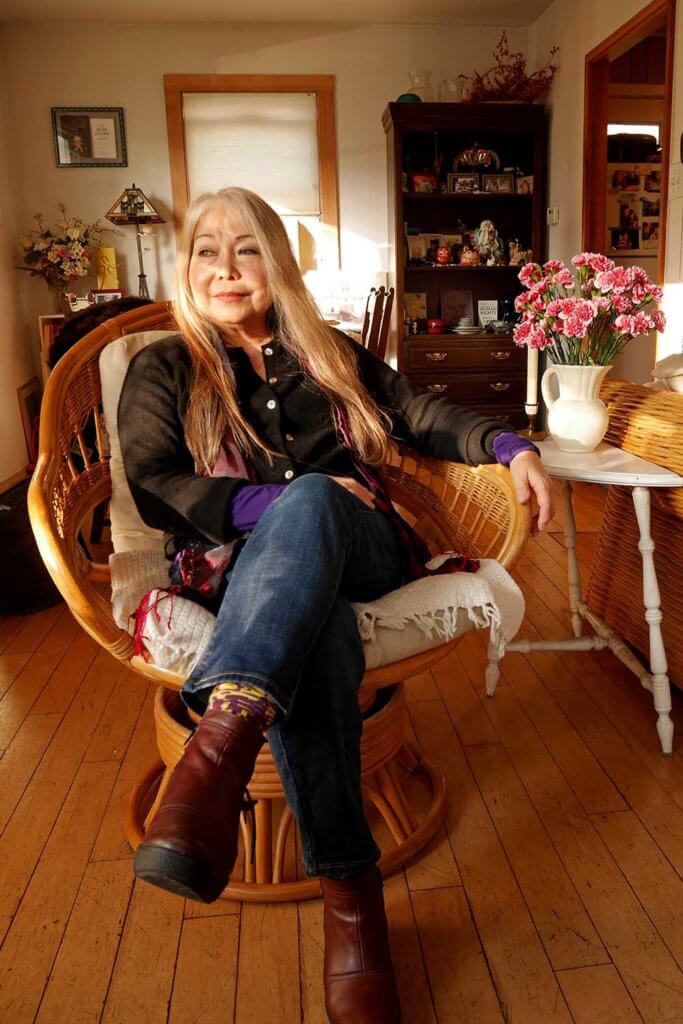

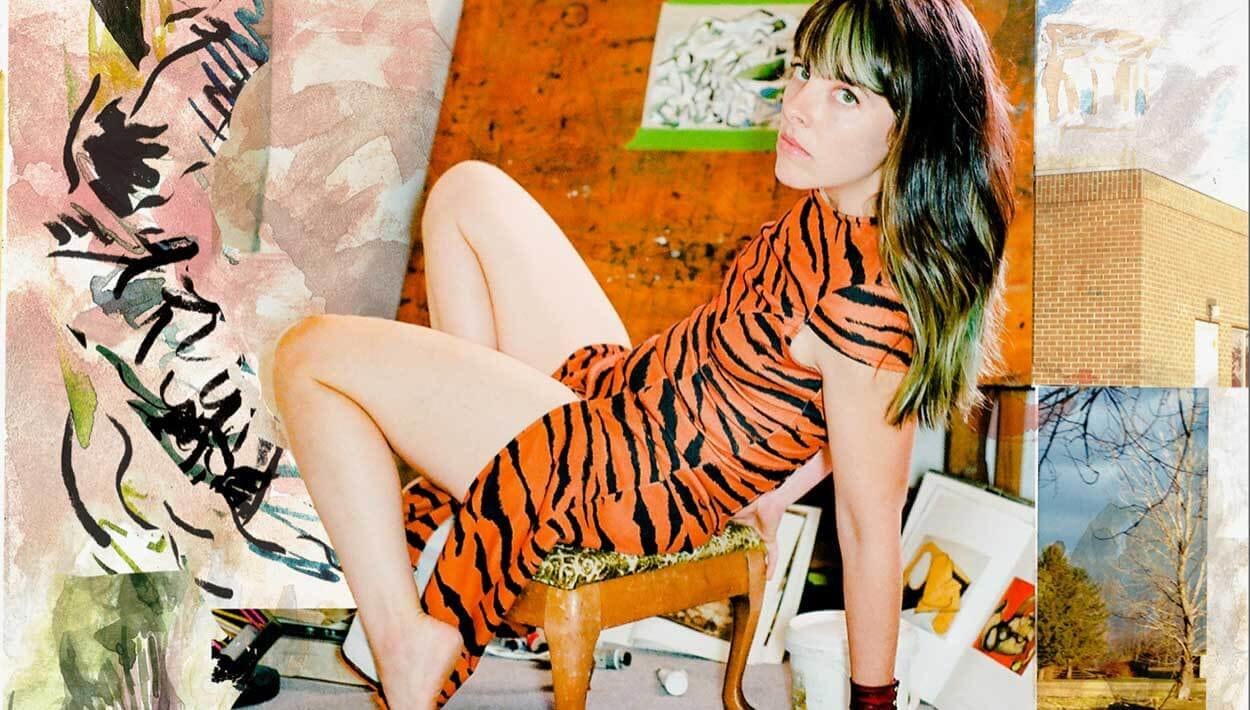

Recognized as Japan’s first female singer-songwriter, Sachiko Kanenobu enjoys the fruits of her labor 40 years after the release of her debut album, Misora.

“I can see the sun peeking through the clouds a little bit,” responds Sachiko Kanenobu when I ask how she’s doing. This doesn’t come as a surprise when considering Kanenobu’s 1972 debut album, Misora. The sky is imperative to her work and well-being—she even ends our conversation with, “Big sky love to you”—and chooses to keep her definition of ‘misora’ as vast as the blue above.

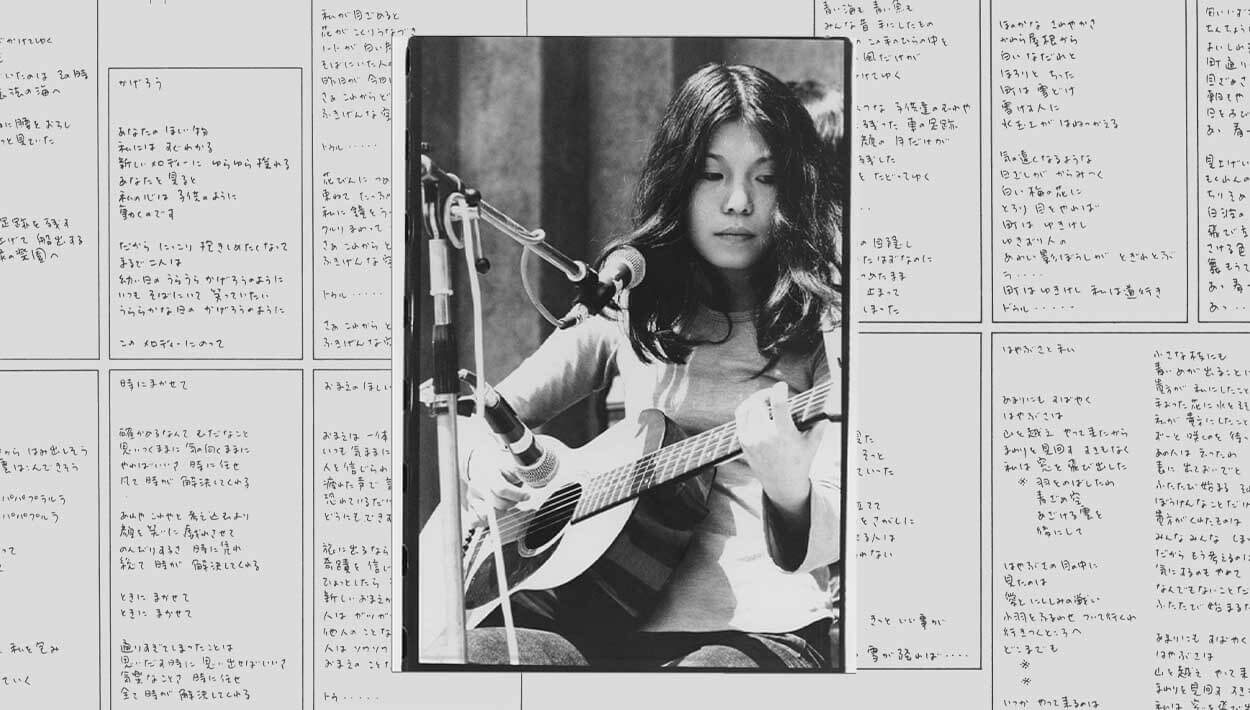

“Misora is a place, it’s a sky,” she writes in the booklet that accompanies the reissue (and first ever US release) of Misora, released last year by Light in the Attic. “It’s a place you can go and be creative. Misora has so many different meanings… I didn’t want to put the meaning in there. Open sky, actually. Sky, meaning the inside of myself, and my mind, my creative mind. And emotion. It’s like the sky also has emotions—rain, crying about it; storm, feeling very angry.”

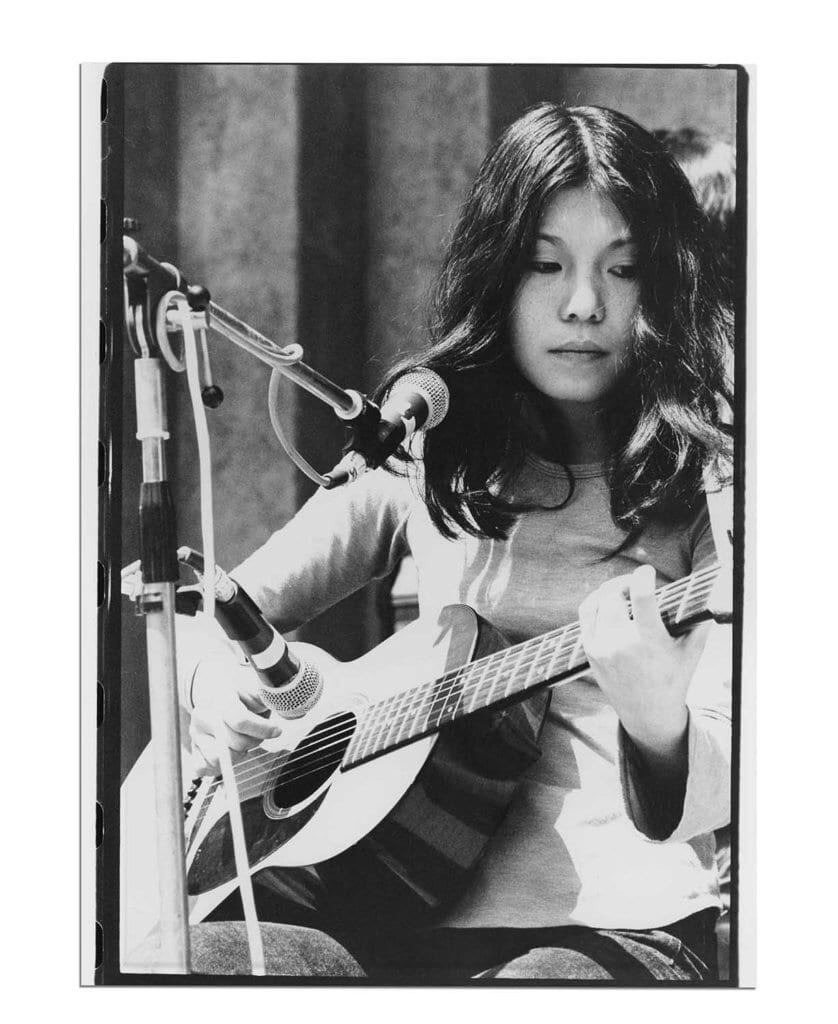

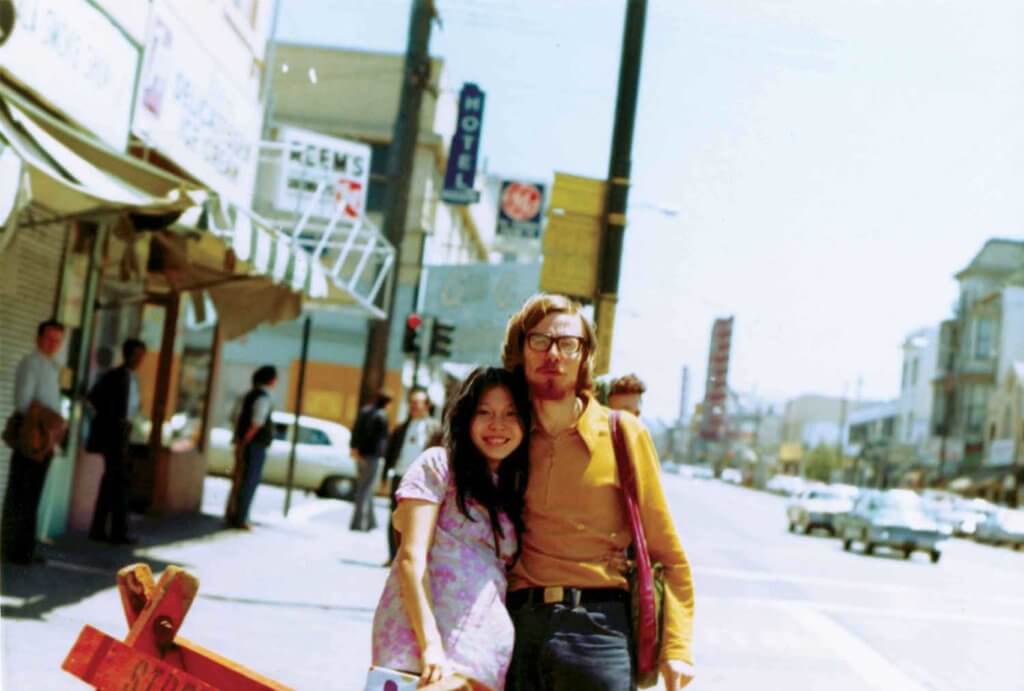

Kanenobu speaks with me by phone from her Sonoma Valley home in Northern California, where she’s lived for the last 40 years. Born in Osaka, Japan, Kanenobu originally released Misora in 1972 on Tokyo’s Underground Record Club. Her lyrics are poetic, filled with natural wonders and small details of her days, while her guitar playing is delicately finger-picked through alternate tunings.

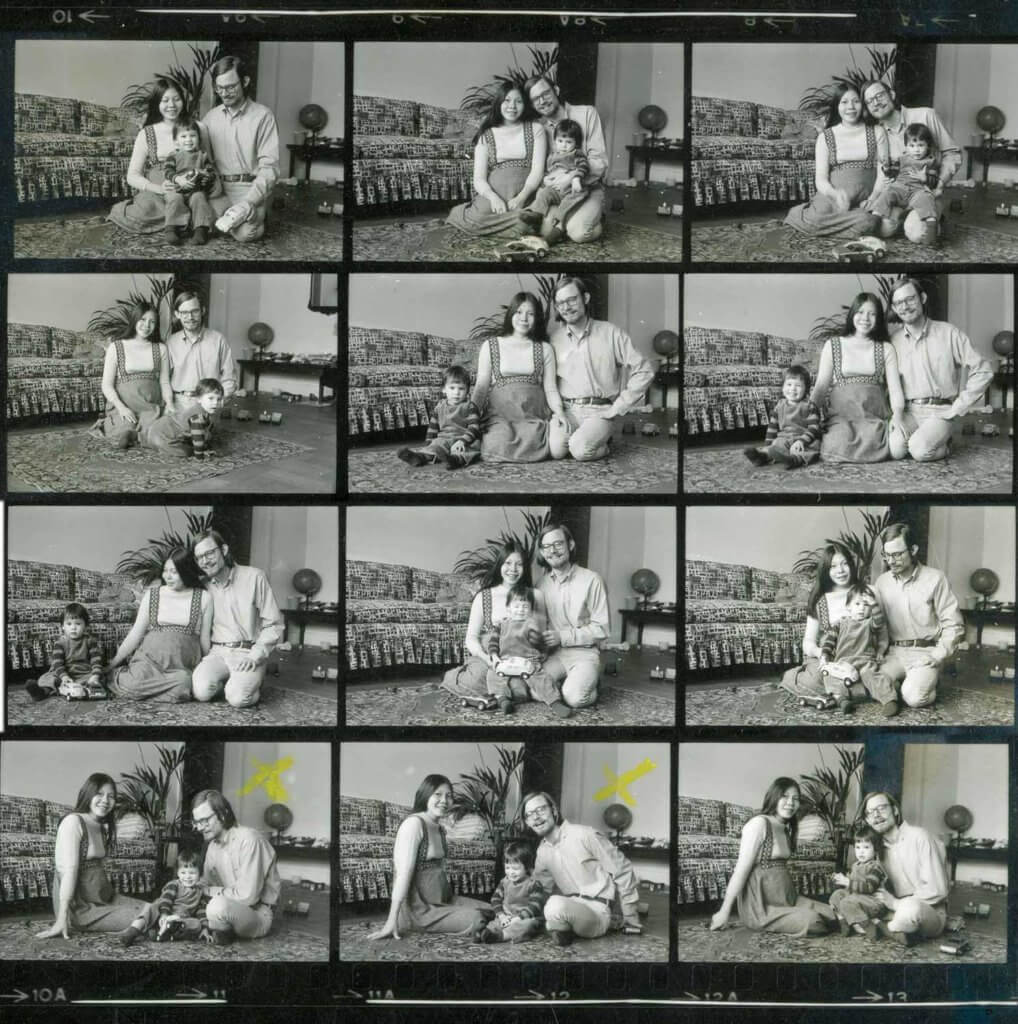

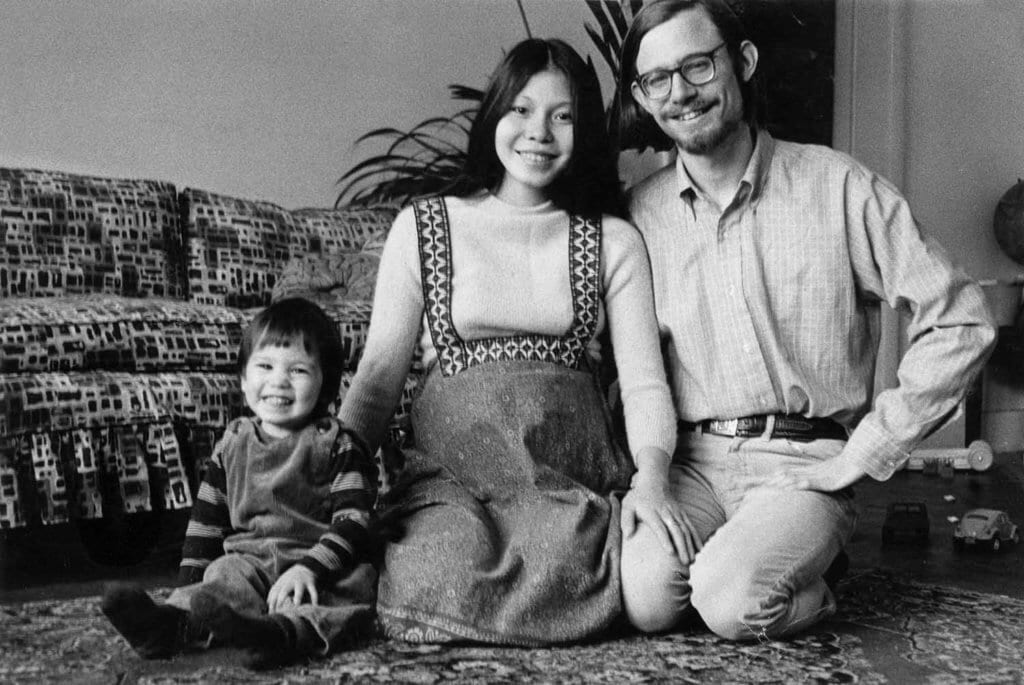

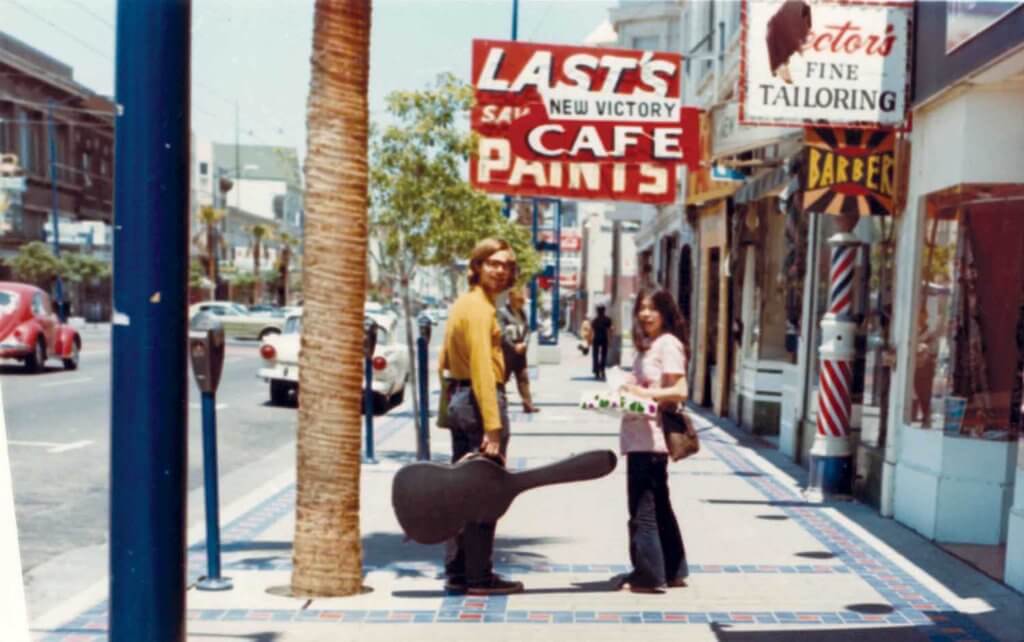

However, Kanenobu left Japan for California before Misora was released, to start a life with her then husband, music writer Paul Williams. Without the musician to promote it, the debut album went into hibernation for decades.

Today, Misora is finally getting the attention it deserves, and so is Kanenobu. She is often regarded as Japan’s first female singer-songwriter, and has been touring the US and Japan to euphoric fans—young and old—who have waited their whole lives to see her perform the cult album.

For Kanenobu, the sky is limitless.

Can you talk a bit about what brought you to the guitar in the first place, and how you learned to play?

One of my brothers was learning about classical guitar playing, and I used to watch him. He got tired of playing, left his guitar in his room, and I asked him if it was okay to touch his guitar. He said, “Okay, be careful.” [Laughs.]

At first, I was just messing around. And then, a friend of mine in high school, she told me to go to Kansai University in Osaka [where] they had a folk club. Most of the students of folk club were outdoors, practicing folk music. So we did sneak in, pretending we were students. [Laughs.] There was a really great guitar player there, [Ichizo Seo], who taught me how to play. I didn’t go to any music school, not learning scales, nothing. I just did it by hearing and watching people play.

You’re quoted as saying, “Sometimes, you can create something special from the unknown, [rather] than when you go to school and have to do it this way or that way. Like learning from hearing—it’s a more basic, ancient way of creation. You’re not writing anything down.”

Well, because I’m very lazy. [Laughs.] I don’t want to learn, or write anything down. I have good ears, and I was very sensitive about music when I was very young. My sister played Beethoven and Mozart, and when I heard something really minor toned—you know, very sad melody—I cried. But if the music was really happy, I had to skip around. I was a very passionate person, and still I am. I don’t feel like my age, so much—I’m 71 years old.

What was the music scene like in Osaka when you first started playing?

Not so many folk singers, but there was the major folk singers, like Ryoko Moriyama. She was covering Joan Baez songs… Peter, Paul, and Mary songs, you know? No one did any writing of their own songs. But at the folk club, they were really interested in American folk music, all the great folk singers. And so, they would start imitating those people. And then, one of the students, Ichizo Seo, he became a very big, famous arranger in Japan—and a very good friend of mine. He showed me how to play, and introduced me to Donovan and other British groups.

“In Japan, when I played last year and this year, mostly young people came up to me to say, ‘I was a big fan of you since I was in my mom’s stomach!’ That’s how they became Misora fans, because their mother or father listened to it. I couldn’t believe it.”

_______

Later, I wrote my first song in middle or high school. A friend of mine wrote the lyrics and I wrote the melody on the guitar. I had three women friends, and we’d recreate [the songs of] English bands after school—that’s it, we didn’t perform or anything.

I wasn’t playing guitar then; I was playing drums. I love rhythm, and that brought me to the guitar, which can also be a rhythmic instrument. You can play melody or rhythm, and that’s what really got me into guitar. But I have very small hands and short fingers, so I have to manage a different way to play.

That led me to Takashi Nishioka from the group Itsutsu No Akai Fuusen (5 Red Balloons) in Japan. He showed me Joni Mitchell’s first record, [which] I’d never heard before. I was into Okinawa scales, very interesting scales, but totally different from Japanese style. And Joni Mitchell has a little bit of Okinawa, too. I tried to copy Joni Mitchell, but it’s impossible. Later I found out she was playing in open tunings, and I didn’t know open tunings at all—I did everything on regular tuning on Misora.

What guitar did you play on Misora?

I recorded Misora with a 1964 Martin that I found it in a pawn shop around 1969 (but Steve Gunn told me a few times it’s older than that, but I don’t know exactly)—and I play that guitar still now. But I don’t want to bring it on tour so much, because it’s a lovely guitar. And if I die, I’m going to die with this guitar. [Laughs.] It’s part of me, and so I’m going to look for another guitar for touring.

Misora is such a beautiful record—musically and lyrically. In the ‘80s, Philip K. Dick encouraged you to write lyrics in English. I’m wondering what that experience was like, and if you felt like you were you able to fully express yourself?

Phil told me to write in English, and my ex-husband, Paul [Williams], told me, “If you want to do music in America, you have to write in English so people can understand.” I was only 20-something, still a kid, and I was so shy. I couldn’t say direct words in the songs, so much.

When I moved to the United States, I found out how different the culture is from Japan. A woman is still kind of behind a man in Japan: shy, and they can’t say what they want. But a woman in America is not like that, [they are] really expressing themselves. So my songwriting is changed.

Plus, living with Paul, he was a music critic and listened to a lot of rock music, so I did too. A lot of Bob Dylan, and when I read his lyrics it just blow my mind. He explained himself so fantastic, it influenced my English songwriting a little bit. So I started writing English songs, and in 1980 I recorded my first American 45 single, “Fork In The Road / Tokyo Song,” in English—with the encouragement and support of Philip K. Dick. Then in 1987 I released my first indie four-song EP, Sachiko Culture Shock, on my own label LXR.

In the liner notes to the 2019 U.S. releases of Misora, you wrote about what ‘misora’ means to you, and how you don’t want to define it. Can you talk a little bit about that?

On Misora, there’s a love song I wrote—”Kagero (The Heat Wave).” In America, [love songs were like], “I love you, I make love to you.” But in Japan, you couldn’t say that. So all those kinds of things are in that song, but I don’t explain so much because people take things differently, and that is the beauty of the song.

The only direct words I said on Misora are on “Omae No Hoshii No Wa Nani (What Do You Really Want?)” That song is very straight-forward.

What has re-learning songs you wrote over 40 years ago been like for you? And to be playing them to a younger generation who only recently discovered your music?

It’s very, very interesting. It’s a miracle. In Japan, when I played last year and this year, mostly young people came up to me to say, “I was a big fan of you since I was in my mom’s stomach!” [Laughs.] That’s how they became Misora fans, because their mother or father listened to it. I couldn’t believe it.

When Misora came out, much later [when] I was already in the United States, some people told me that Misora is boring, puts [them] to sleep. [Laughs.] So in America, I couldn’t believe it—the singer-songwriter, Steve Gunn, asked me to open for him. In San Francisco, during my second performance, I came out in regular clothes. I forgot my makeup and stage clothes, I forgot everything. But everyone was clapping, and I was like, “Whoa, what? Are you kidding?” I was really surprised to see that. Some people remembered [the songs], especially “Anata Kara Toku E (Far Away From You).” When I started playing it, they started clapping, and I thought, “Wow! Where did these people come from?”

I left Japan before they released Misora, and no one heard it [in America] for decades. Last year, when I went back to Japan, the people couldn’t believe I was still alive, and some young people thought I am an alien from another planet. Not human. ‘How can a 71-year-old woman play the 1972 whole album?’

That’s the fantastic, miracle part: I just remember all the chords and lyrics. It’s in my head. I’ve never written down, in my notebook or any place. With my original Misora guitar, we made some kind of spiritual connection. It just came out. In Japan, this time, I did a short tour of Tokyo, Osaka, Kyoto—the [venue’s were] packed, so many young people. Here, in America, too. I’m very fortunate I can play in front of those people, and that they love Misora.

How amazing to finally see the fruits of your labor…

Yes! People in the audience were crying. I was singing “Toki No Makasete (Leave It To Time)” and they were singing with me, with tears in their eyes. I had tears in my eyes, too.

You May Also Like

No related posts

No related posts

More posts

-

By: Cynthia Schemmer

-

By: Jenny Lim

-

By: Allison and Katie Crutchfield

-

By: Fabi Reyna

-

By: Cheri Amour

-

By: Stephanie Mendez

-

By: Cynthia Schemmer

-

By: Steph Wong Ken

-

By: Bean Tupou

-

By: Eleanor Linafelt

Comments

thanks for sharing

Comment by kishore on August 24, 2021 at 3:45 amSachiko Kanenobu is a retired Japanese woman who lived in the United States for many years. One of her lifelong passions was writing, and she loved to write about the sky. In fact, she wrote a book about how to make the best use of the sky with the sky-watching tips and tricks that she had learned over her lifetime with the help of https://knowtechie.com/the-best-free-apps-that-write-essays-for-you/ article. Kanenobu writes about the importance of sky watching and how it can help you relax.

Comment by Jessica on September 26, 2022 at 12:24 pmI am doing research on Paul Williams for a book and would like to speak to you about him if possible. Thank you

Comment by Elisabeth Rosenberg on May 28, 2023 at 2:12 pmThanks for sharing, This interview is so inspirational. She’s a wonderful woman

Comment by Gamblorium Canada on August 9, 2023 at 6:34 amI believe everyone can discover something suited to their interests here. Best of luck!

Comment by Delta Executor on February 20, 2024 at 12:39 am