The History of Murder Ballads and the Women Who Flipped the Script

Originally, murder ballads focused exclusively on homicide—and often that of women. We dig into the history of the subgenre, and the women who reclaimed it.

Murder ballads are everywhere. From songs, to movies, and beyond, the centuries-old subgenre is ingrained in our culture—and sometimes, we may not even pick up on the violent, and often misogynistic, messages.

You may have encountered murder ballads in the podcast Dolly Parton’s America, in which an entire episode it dedicated to how they influenced Parton’s earlier albums, and how she became a feminist icon by flipping the script; on The Hunger Games soundtrack, in which the foreboding song “The Hanging Tree” draws from Appalachian folk; the bluegrass standard, “Pretty Polly,” which has been performed by everyone from jazz guitarist Bill Frisell to Judy Collins to Throwing Muses frontwoman Kristin Hersh; or songs like “Hey Joe” (popularized by Jimi Hendrix), “I Used to Love Her” by Guns N’ Roses, or “Love the Way You Lie” by Eminem (featuring Rihanna)—all of which may not strictly follow the murder ballad formula, but continue the violent lyrical tradition.

However, there’s an entire history of women performing traditional murder ballads, as well as writing some of their own, as an act of taking ownership of a tradition that often kept them defeated and, well, dead.

But first: what are murder ballads?

Originally, the murder ballad subgenre sprung from the ballad tradition, a narrative song form that often depicted an event (in the case of murder ballads, the killing is the event). While many ballads remembered and performed in the US today largely originate from the British Isles, there are various ballad traditions from all over Europe. And in the US, many murder ballads come out of Appalachia, where the majority of the early settlers were from the Anglo-Scottish border country.

In this context, ballad has a different meaning from modern day musical parlance; historically, it’s a song or poem that chronicles a particular story, with or without music. Broadside ballads were poems about real events that were printed and distributed to the public. Eventually, there were melodies added to some of these poems, and many renditions were performed by an array of musicians, which accounts for the variations of these songs (often with no known author) that one might hear today. These broadside ballads were used to make money, chronicling a crime and sometimes sold as souvenirs outside of court houses. They also acted as a way to convey information throughout communities—and in some ways, they were almost like tabloids.

What many listeners don’t realize is that traditional American murder ballads often depict the real and true murder of a woman. Many were pregnant, often slain by the father of their unborn child (maybe their lovers were already married, or of a different social standing, and these women became a problem that needed to be taken care of)— in any case their pregnancies apparently made them inconvenient and disposable.

Murder ballads focused exclusively on homicide, and often the homicide of women. They were sung and written from various points of view: Sometimes the killer expressed their remorse (“Banks of the Ohio”), other times the victim sang from beyond the grave (“The Twa Sisters”), and in some songs the narrator was omniscient and removed from the direct action of the story (“The Ballad of Pearl Bryan”). The women in these songs were perceived as innocent, helpless victims who were “led astray” by their lovers—who, more often than not, were also the murderers—powerless against their fate. The messages of these songs were heard as warnings to other young women of the time to not to go down the same path, while the men were often portrayed in a bizarrely sympathetic way, seemingly not responsible for their own actions, but rather co-victims in these “crimes of passion.”

Murder ballads based on true stories turned real-life victims into narrative stereotypes, warning other women what would happen if they “misbehaved”—in other words, women engaged in their rightful autonomy while men disturbingly pushed back. This, in turn, fed the public curiosity of violence as entertainment, and perhaps was one of the earliest forms of true crime media that is so rampant today.

“The murder ballads witness that Appalachia, specifically in the 19th-century period of industrial change, was defined by essential tensions between cultural traditions of the past and emerging notions of American modernism. This tension is met in the songs with responses of violence against women whose life situations—marked by sexual freedom—are the very depiction of a new cultural modernism that threatens the hegemony of the past.”

“‘This Murder Done’: Misogyny, Femicide, and Modernity in 19th-Century Appalachian Murder Ballads.”

One of the most famous murder ballads, “Omie Wise,” tells the story of the 1808 murder of Naomi Wise, who died in North Carolina. While the actual facts of this case are lost to history, according to folklorist Eleanor R. Long-Wilgus, it was suspected that John Lewis, who was thought to be the father of Naomi’s unborn child, killed her. It is believed that Naomi may have been older than Lewis and knew that he was engaged to be married to someone else. When Naomi became pregnant, it appears that her fate was sealed. In one of the most famous versions of the song, by guitarist and singer Doc Watson, the lyrics state:

John Lewis, John Lewis, will you tell me your mind?

Do you intend to marry me or leave me behind?

Little Omie, little Omie, I’ll tell you my mind,

My mind is to drown you and leave you behind.

Have mercy on my baby and spare me my life,

I’ll go home as a beggar and never be your wife.

Meanwhile, “Pearl Bryan,” another well-known and particularly gruesome ballad about the killing and beheading of a pregnant 22-year-old Indiana woman in 1896, does not usually reference her pregnancy, but it does refer to her alleged killer, Scott Jackson, as her beloved:

What have I done Scott Jackson that you should take my life,

I’ve always loved you dearly. I would have been your wife.

While dozens of songs recounting the murder of Bryan have been recorded, they all vary in the way the story is told. The real story, according to folklorist Sarah Bryan (no relation), began when Bryan contacted Scott Jackson, whom she believed could be the father of her unborn child. With the help of Alonzo Walling, it’s been speculated that the two either brought her to a doctor in Cincinnati who mishandled the abortion, or Jackson and Walling, using what they learned in dental school, attempted to perform the procedure and failed, resulting in her death. The two brought Bryan to Kentucky and disposed of her body, but not before beheading her as an attempt to prevent identification. Jackson and Walling were eventually caught, found guilty, and sentenced to a double hanging.

The Women Who Flipped the Script

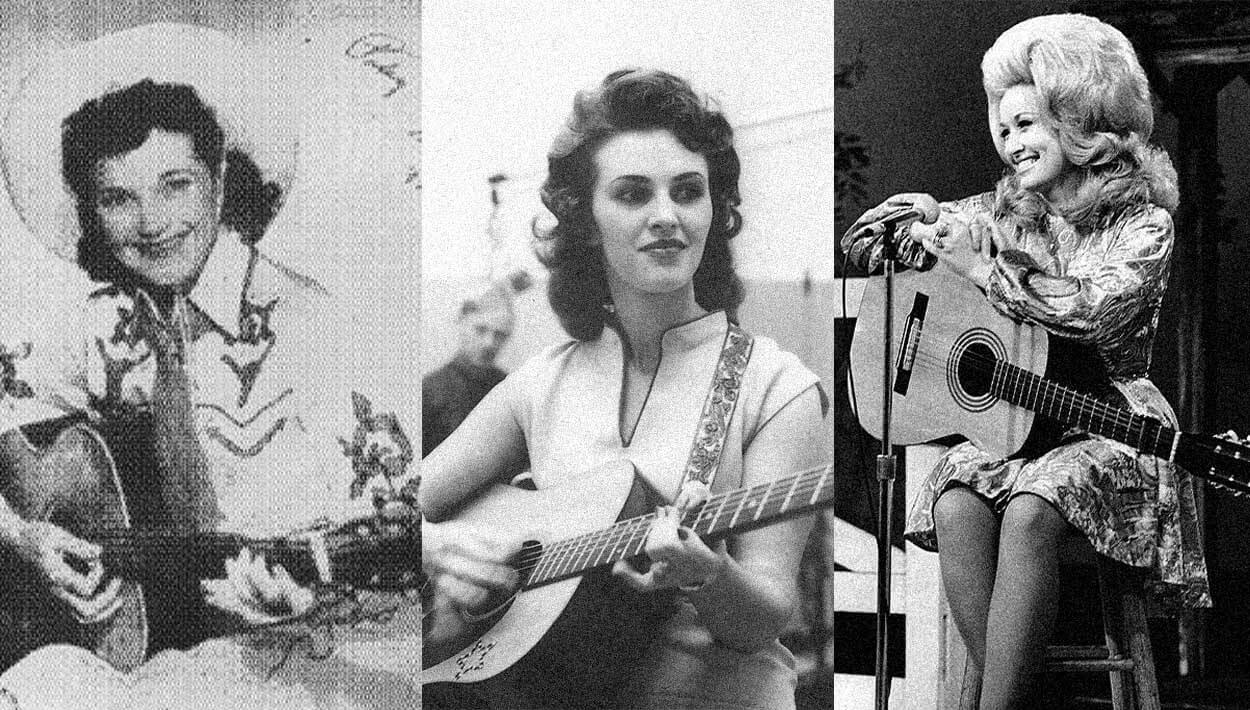

As the 20th century carried on, murder ballads continued to burrow their way into the American consciousness. And not surprisingly, women stepped in and put their own stamp on this tradition, turning the tables and questioning the status quo of murder ballad lyrics. In the 1920s and 1930s, many traditional murder ballads had made their way into the collective folk/country/bluegrass repertoire, resulting in them often being sung by women.

In 1924, North Carolina musician Eva Davis, along with friend and fellow musician Samantha Bumgarner, traveled to New York City to record some songs, including the murder ballad, “John Hardy” on banjo. The song can be traced back to West Virginia, where it’s believed that John Hardy killed Thomas Drews in a disagreement over a game of craps.

Following in 1928, the Carter Family, with Maybelle Carter on guitar, recorded a variation of the song, titled, “John Hardy Was a Desperate Little Man.” Maybelle Carter, with her distinctive style of playing called the “Carter Scratch,” influenced legions of guitarists, and her iconic Gibson L-5 sits in the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville.

In the late 1930s, the Coon Creek Girls, an influential all-women string band that appeared regularly on the Renfro Valley Barn Dance radio program, recorded the murder ballad “Pretty Polly.” The song has roots dating back to the 1760s, and its impact is still felt today with versions heard on television shows such as House of Cards and Deadwood. The Coon Creek Girls, along with singer Idy Harper, also recorded a variation of “Omie Wise,” titled “Poor Naomi Wise.” The group featured Lily May Ledford, Rosie Ledford, Esther “Violet” Koehler, and Evelyn “Daisy” Lange. Lily May Ledford enjoyed a resurgence in her career during the folk music revival of the 1960s, and was awarded a National Heritage Fellowship before she passed away in 1985.

It wasn’t until around the 1940s when women began regularly reclaiming murder ballads as their own, writing and recording original music and putting women in positions of power.

Patsy Montana, who was the first woman recording artist to have a million-selling record with, “I Want To Be A Cowboy’s Sweetheart,” had another tune in her repertoire with a decidedly darker bent. “I Didn’t Know the Gun Was Loaded” tells the story of a murderous, gun-toting femme fatale, Miss Effie. Written by Herb Leventhal and Hank Fort (who was born Eleanor Hankins), the song was recorded by several different artists in 1949, with notable versions by the Andrews Sisters and Montana. The second verse is positively revolutionary for a song recorded at the time, as it could be interpreted as Miss Effie shooting a man who tried to rape her:

Now one night she had a date,

With a wrestling heavyweight.

And he tried a brand new hold,

She did not appreciate.

So she whipped out her pistol,

And she shot him in the knee,

And quickly, she sang this plea.

I didn’t know the gun was loaded,

And I’m so sorry my friend.

I didn’t know the gun was loaded,

And I’ll never, never do it again.

In 1966, rockabilly and country pioneer Wanda Jackson recorded another song of revenge, “The Box It Came In.” Written by Vic McAlpin, the song peaked at #18 on the Billboard Hot Country Songs and spent 11 weeks on the charts. In her autobiography, Every Night is Saturday Night: A Country Girl’s Journey to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, Jackson wrote, “In 1966, Capitol released ‘The Box It Came In,’ which was my first Top 20 country single since 1961. That was one Ken Nelson [producer] was a little worried about because of the subject matter.” She felt strongly about the song, adding, “I thought it was great, but Ken was always a little scared of courting controversy. I always like feisty songs, so I convinced him we should do it.”

My clothes are all ragged my goodwill coat’s not the best,

And I’m a walking on cardboard in my last dollar dress.

I looked in the closet for my wedding gown,

But the box that it came in was all that I found.

He took everything with him that wasn’t nailed down,

Bet he’s got a new sweetheart to fill my wedding gown.

But somewhere I’ll find him then I’ll have peace of mind,

And the box he comes home in will be all satin lined.

Dolly Parton is a trailblazer in many ways, and her contribution to murder ballads is no exception. Her first four albums, recorded in the late 1960s, delve into the reality of life for women in a way that not many had done. Helen Morales, Argyropoulos Professor of Hellenic Studies at UC Santa Barbara, author of Pilgrimage to Dollywood, and guest on Dolly Parton’s America states that Parton’s songs “provide an insistent witnessing of women’s lives,” and speaks about “women being treated really badly by men.” During her career, Parton has covered traditional ballads including “Banks of the Ohio” (also covered by Joan Baez, who was known to often perform murder ballads) and “Silver Dagger,” but in 1967, she wrote the murder ballad, “The Bridge.” The song is told from the perspective of a woman who falls in love with a man under a bridge. He gets her pregnant and flees, resulting in the woman returning to the bridge to commit suicide: “Here is where it started, and here is where I’ll end it.”

Murder Ballads Today

Many contemporary songwriters have drawn inspiration from these old stories, creating their own modern day murder ballads. And women, specifically, continue to subvert the violence in both subtle and overt ways.

One of the most famous murder ballads, written at the end of the 20th century, is the Dixie Chicks’ righteously revengeful “Goodbye Earl,” in which lifelong best friends, Mary Ann and Wanda, kill Wanda’s abusive husband. The song was controversial for its time, and some radio stations refused to give it airtime—according to the LA Times, about 20 out of the 149 radio stations tracked by Radio & Records refused to play the song when it was released.

But what makes this song different from other murder ballads is its happy ending: Maryann and Wanda open up a roadside stand and face zero consequences from the murder of Earl, because, as the songs states, “It turns out he was a missing person who nobody missed at all.” The video won the Academy of Country Music and Country Music Association award for Video of the Year, and some radio stations that did play the song often aired it alongside messages that referred domestic violence victims to hotlines for support.

On Gillian Welch’s 1998 album, Hell Among the Yearlings, the singer-songwriter, along with David Rawlings, contributed a new staple of the murder ballad genre with the song “Caleb Meyer,” in which a woman kills her rapist while he’s attacking her. The song does not present any easy answers, and the narrator wrestles with what she did out of self defense:

Caleb Meyer, your ghost is gonna

Wear them rattlin’ chains.

But when I go to sleep at night,

Don’t you call my name.

Valerie June’s “Shotgun,” released on her 2013 album, Pushin’ Against A Stone, tells the story of a jealous lover who kills their cheating partner and then kills themself. This visceral, bluesy track features June’s stirring guitar work and haunting vocals.

Again, moral ambiguity is on display; an unfaithful lover is met with revenge. In an interview with NPR, when asked about writing “Shotgun,” June responded, “Many times in the older songs, the woman’s the one to die. And I was like, no, no, no—it can’t always be that. We have to balance out the murder-ballad situation.”

Perhaps one of the most notable modern songs to address murder ballads is Hurray for the Riff Raff’s “The Body Electric,” released on 2014’s Small Town Heroes. Songwriter Alynda Segarra uses the song to address how our culture treats violence with detachment, especially violence against women, and she expertly frames this by pointing to the casual violence of murder ballads: “While the whole world sings / Sing it like a song / The whole world sings like there’s nothing going wrong.”

“I am mostly familiar with how [‘The Body Electric’] has taught me there is a true connection between gendered violence and racist violence. There is a weaponization of the body happening right now in America. Our bodies are being turned against us. Black and brown bodies are being portrayed as inherently dangerous. A Black person’s size and stature are being used as reason for murder against them. This is ultimately a deranged fear of the power and capabilities of black people. It is the same evil idea that leads us to blame women for attacks by their abusers. Normalizing rape, domestic abuse and even murder of women of all races is an effort to take the humanity out of our female bodies. To objectify and to ridicule the female body is ultimately a symptom of fear of the power women hold.”

“The Political Folk Song Of The Year,” NPR

Musicians today are creatively reckoning with the ghosts of American folk music. Women are taking control of a narrative that was once physically and creatively forced upon them, and pointing out the hypocrisy of the detached view of violence—in fact, on International Women’s Day in Middletown, Connecticut, a group of musicians did just that.

With funding from a REGI Grant (Regional Initiative Grant Program) from the state of Connecticut, I organized the event, The Murder Ballad Project: Reframing Songs of Violence, as a response to my lifelong fascination with murder ballads and their place in our culture. I invited some of my favorite artists from the region, including Rani Arbo, Pamela Means, Lara Herscovitch, Amanda Monaco, and Karen Dahlstrom to perform both murder ballads and songs of empowerment. We partnered with New Horizons Domestic Violence Services to raise money for them, but to also provide context that the violence women faced in murder ballads is still very much a reality.

My hope is that if we look at the violence in these songs head on, without a sense of detachment or denial, then maybe our collective resignation to violence will change. I was humbled to be a part of the long tradition of women taking what has been given to them—in this case, murder ballads—and flipping the script.

Comments

Two Kentucky songs flip the script. One is old, “False Sir John,” Jean Ritchie’s version of “Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight” of British tradition. One is new, “Little Omie’s Done Got Wise,” written and recorded by the Reel World String Band.

Comment by Rich Kirby on March 18, 2020 at 9:31 amThis is a great article! I have an entire EP of murder ballads called “7 Deadly Spins” and the inspiration was to provide more of a a “female perspective” on the genre. Focusing more on the story and less about the killing. Love this!

Comment by Lynne Hanson on March 19, 2020 at 4:58 amI grew up listening to my grandmother singing these sad ballads–she grew up in Kentucky and sorta lived that life. This is a great article–thanks so much–brought back lots of memories

Comment by Sally Tibbetts on March 19, 2020 at 6:53 amYou’re forgetting the english murder ballad queen, Sarah Vista! She’s been blazing a scorching trail and just won an Aneripolitan award for her unique songwriting skills..

Comment by Mike B, England. on March 19, 2020 at 7:37 amIn a 1981 Halloween sketch on Saturday Night Live, Christine Ebersole sings the ballad “I’m So Miserable” as an abused wife who murdered her husband. https://www.nbc.com/saturday-night-live/video/im-so-miserable/n8859

Comment by Joel Shprentz on March 19, 2020 at 9:06 amMiss Izzy Cox ” am a bad bad woman” Dead or Alive”

Comment by Connie on March 20, 2020 at 5:55 pmMiss Izzy Cox ” am a bad bad woman” Dead or Alive”

Comment by Connie Cox on March 20, 2020 at 5:56 pmWhat about “where did you sleep last night?” It is on Nirvanna unplugged, originally Leadbelly?

Comment by Melissa on September 20, 2020 at 10:57 amObjectivity should remain as a goal when writing history and making analysis. Instead we get typical infantile feminist rantings mixed with real stuff, annoying to say at least.

.

For example, you said that men are presented in some bizarre sympathetic way in these songs, like they are not responsible for their actions. Are you actually listening these songs in a proper context or do u apply some random feminist interpretation on top of it ? If the culprit shows remorse or is be hanged or whatever, THEN they are being hold responsible.

What you mean to say is that in these songs men are not JUDGED in a manner modern society judges men and therefore it doesnt satisfy your poor feminist soul ?

Would be nice article but impossible to read due the rampant feminism.

Adult thinking people dont need to be preached , especially about some random ideological POV, which feminism is, its an interpretation of reality, one of many and as such does not present the “truth”

Feminism ruins everything. Nuff said.

Comment by jack on April 12, 2021 at 7:11 amA minuscule white penis was behind that last comment. What are you even doing here dude? This website isn’t for you, and clearly no one cares about your opinion (which also doesn’t represent the “truth” and is actually quite biased). This isn’t a scholarly article, but the author did their research and presented it fairly alongside their own personal experience and viewpoints.

My question is whether /you/ read this article in its proper context or if you applied some random women-hating interpretation on top of it. Also, do you even know any women? Do you even care about their experiences or opinions or hardships? Do you treat the women in your life (if you could be so lucky) with patience, kindness, and understanding? My guess would be no to all of those questions. It makes a lot of sense that you would be sympathetic to how “crimes of passion” were viewed and dealt with in the past.

So, Jack, learn how to use proper grammar and punctuation, learn how to respect women, and go outside to touch some grass instead of whining on a website that has nothing to do with you.

Comment by jack doesn't know jack on May 18, 2021 at 2:15 pmI can see why it was omitted, but I think “The Ballad of Monongahela Sal” would also be of interest to readers of this article. It’s author is unknown and I can’t find any true story it was based on but it tells the story of innocent country girl seduced by a riverboat pilot in a fancy sporting coat who throws her overboard while she is asleep. Instead of drowning though, she swims to shore, hops a freight, steals a gun (from a yard bull who tried to molest her) beats the riverboat to the next town and well, she sure messed up that fancy sporting coat. https://www.traditionalmusic.co.uk/folk-song-lyrics/Monongahela_Sal.htm

Comment by John Baker on June 26, 2022 at 4:22 pmUpon hearing Pretty Polly for the first time by Pete Segar, I started a journey of research into that song, and then on to the murder ballad genre. Just read this excellent article today, in July 2023, and everything suddenly fell into place for me. Thanks for writing!

Comment by Rick Wade on July 11, 2023 at 11:08 amWomen with guns is one of my favorite “moves” in songwriting to be fair! Me and my wife used to buy guns from https://gritrsports.com/guns/ every month in our early days(and shooting at the range together).

Comment by Jim on September 25, 2023 at 12:23 am