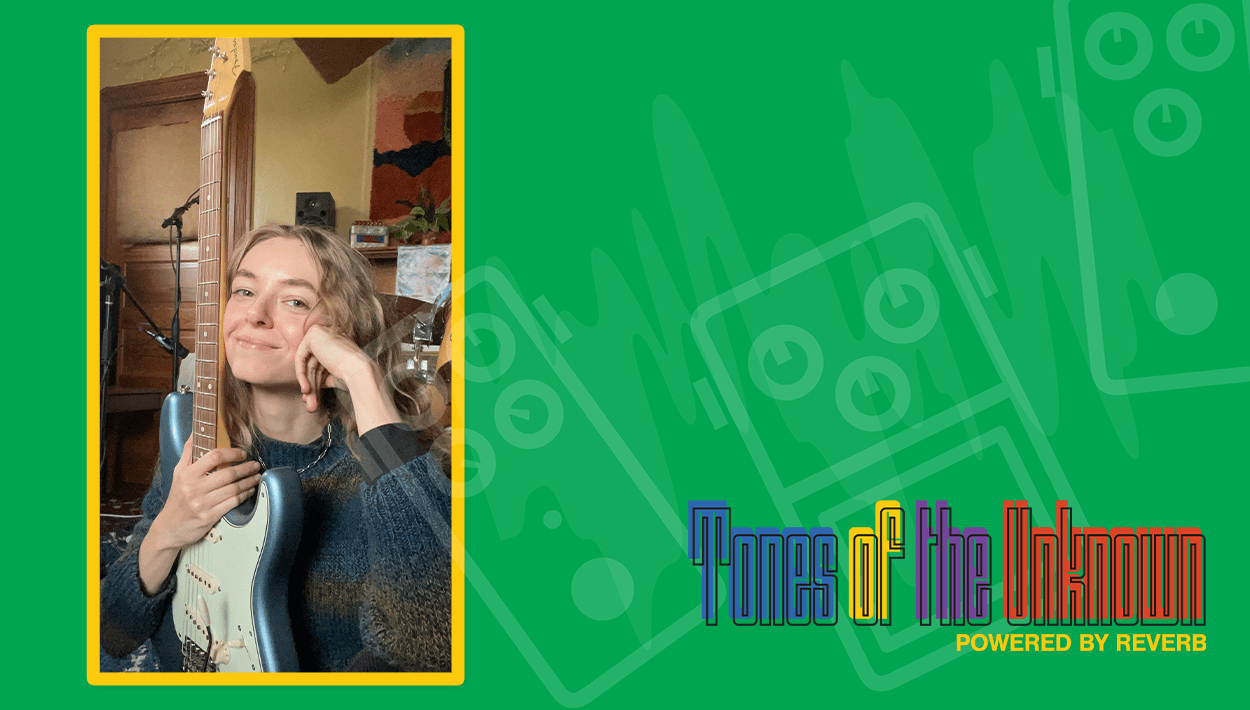

Bedouine and the Power of Setting Her Music Free

Azniv Korkejian of Bedouine offers up her beginner’s mind with guitar, building soundscapes, and working on her sophomore release.

This interview originally appeared in She Shreds Magazine Issue #18, released August 2019.

Recording an album can often feel like setting a particular time of your life into stone. The necessary exposure and permanence can feel emotionally turbulent. But Los Angeles-based Azniv Korkejian, who performs as Bedouine, counteracts that dynamic with soft and sturdy confidence. Korkejian’s palpable ease is apparent on her sophomore album, Bird Songs of a Killjoy, released on Spacebomb Records in June. Over 12 songs, Korkejian captures moments of ending and acceptance, like on “When You’re Gone,” an anxious but mellow tribute to the feeling of absence; “Bird Gone Wild,” a testament to the journey of immigration that Azniv’s family took in her childhood; and “Bird,” a reflection on a past intimacy.

On the phone with She Shreds, Korkejian spoke about the agency that came with being heavily involved in the recording and mixing of her own album, and all of the challenges that come with letting an album live and breathe in the world. That can be one of the hardest parts of making an album, but Korkejian understands the power of setting it free.

What is your relationship to the guitar?

I definitely have a beginner’s mind when it comes to guitar. I was classically trained in piano when I was five, and my mom was a little too hard on me, so I quit as soon as I could. I picked up guitar in college and taught myself. It’s been a pretty loose journey for me. I’ve [honed in on] the way I like it to be, but it’s something I want to look more into, getting lessons and actually understanding the instrument. It’s not been super technical; it’s been more [about] emotional navigation.

Is songwriting therapeutic for you?

Songwriting has always been like journaling to me; it’s a form of expression. I like using an instrument that I don’t know backwards and forwards. When I look at the piano, I get completely stunted. I know too much about it so I can’t look at it like a beginner, which is what I love about playing guitar, that I’m always doing it by ear and guessing my way around until something feels good.

Did guitar change or enhance your relationship to music?

It allowed my relationship with music to be more internal and less about agility. When I was playing piano and classical music, it was more about agility, which is really exciting in a lot of ways, and you still have to be emotional no matter how technical or nontechnical it is. But when I picked up the guitar, there was something about having a beginner’s mind that allowed me to navigate more with my emotions or my ear rather than the agility of my fingers or music theory.

What is your songwriting process like?

Writing, for me, is not really regimented. It happens when there’s a feeling I can stand to confront or try to work through. It’s an itch that I need to scratch. I sit down with a guitar and there will usually be a phrase poking at me. On a really good day, I’ll work it out start to finish in one sitting. But what usually happens is I’ll amass thousands of voice recordings, and when I’m in the mood to really massage an idea out, I’ll go back to some of those.

I definitely see the benefit to flexing your songwriting skill like a muscle, but for me it’s more of an intermittent response to an emotional need. When something is really bothering me, or when I feel overwhelmed in a good or a bad way, it’s this overage that I need to put somewhere.

Did any of those voice memos make it onto Bird Songs of a Killjoy?

Pretty much all the songs on the record started out as voice memos. For every one song that makes the record, there has to be about 50 half-finished ideas. All of it is just really slow and steady.

I think about the next record throughout the previous record’s cycle. So by the time I was ready to start working on Bird Songs of a Killjoy, I already had a pretty good idea of what would make it. I don’t write specifically for the next record; I journal along the course of any time in my life. Some of these songs are older, from the time that I was recording the first record, but other songs are more recent.

Do you see distinct differences between your self-titled debut and Bird Songs of a Killjoy? Did you feel a shift in songwriting and technique between the two albums?

It still feels like me, and I definitely didn’t make a conscious effort to make a departure. That’s up to the listener to decide for themselves. Sometimes I’ll talk to people who’ve heard both and they feel like it’s a step up, which is great to hear, but it feels very natural to me.

In terms of songwriting, it’s very much intuitive and I do think I branched out a little bit more. There are some strange chord changes that I didn’t really write early on. I hear some people using the term “jazzy folk” for my first single, “When You’re Gone,” and I guess that is branching out for me.

What was the recording process like for Bird Songs of a Killjoy? How long did it take?

I recorded at the same studio [as the first album], Sargent Recorders, with Gus Seyffert. It was pretty much me and him, and was done in a similar fashion. If anything, it was a little more stripped back. We had some of the same players, like Smokey Hormel and Mike Andrews on some guitar, Josh Adams on drums, and a couple of keyboardists. It was all done to tape and then Gus transferred things into Pro Tools. We both picked at the editing and comping because I’m proficient in Pro Tools—I was a sound editor before I was a musician. It gave me the ability to sweep through the session, and a little bit of autonomy when it came to comping something together or picking a take.

Do you prefer to be more involved in the editing and mixing because of your experience as a sound editor?

I think I’ve grown in the studio. This time around I was a lot more vocal about what I wanted and what I didn’t want. Gus is very much the producer still, and he was on the first record too. In a way, he navigated the very early days, and he’s very invested in the sound of Bedouine. Because we are so comfortable with each other and because I can go in there and get some work done myself, it does feel collaborative.

Of course it’s easier said than done, but I would really recommend to anybody going into the studio with someone who is using Pro Tools to try learning the program for themselves, so that they can take the hot seat and tweak through stuff. But you know, some producers might not be comfortable with that. I’m lucky that I’m working with somebody who I’m so comfortable with and that we can just swap seats for a second.

Did you and Gus work together before your first album?

At first, when I was writing so much, I wanted to put the songs on tape so I could start storing them in a better way than voice memos. I wasn’t really sure that I would release anything, but I knew that I at least wanted to give them a good home. I had known Gus for a while, and had been to his house and noticed all of these tape machines everywhere, so I asked him if I could pick his brain about it. We had a really good talk, and then he asked me to sing through a song in one sitting [and record] to tape because he had everything already set up. So I did, and the very first take is “Solitary Daughter” on the first record. That was the first thing we did [together]. I’m so proud of that. It was the very first step towards [Bedouine]. That carved the way for Gus and I to work together.

Did that moment help solidify a sound for Bedouine?

That did set that tone for the [self-titled] record. I think “Solitary Daughter” inherently doesn’t need very much, and so we started in such a simple fashion. After I put down that first take, Gus put down this really beautiful bassline and then we worked together on the harmonies. And before we knew it, we were done. It was just so special and I’m so happy to have started that way.

On your first album, you have a field recording of your grandmother’s street in Aleppo, Syria, that appears at the end of the song “Summer Cold.” Do you have any moments like that on the new album?

On “Echo Park,” I built a soundscape of Echo Park Lake [in LA]. I went there and took ambient recordings and layered some things on top of it. In the video, there’s a scene where I have a picnic and everybody there is a woman singer-songwriter, and every one of them has their own project. That’s kind of an intentional representation of the East Side of LA and the women who play music here. There’s so many people in LA doing such exciting things.

Comments

The mockup can be used as a placeholder for a cover design, or you can use it to show your book in its entirety.

Comment by stumble guys on September 28, 2022 at 12:58 amThis a very awesome blog post. We are grateful for your blog post. You will find a lot of approaches after visiting your post

Comment by stumble guys on November 15, 2022 at 12:21 amcool bass bit there- not sure where i have heard this clarinet/oboe before..

Comment by pacman 30th anniversary on December 6, 2022 at 8:22 pmThis blog post is very fantastic. We appreciate you writing this article post. Upon visiting your article, you’ll see a variety of options.

Comment by getting over it on April 26, 2023 at 12:07 amThis is an excellent blog post. Your article is really appreciated. There are many choices while viewing your content.

Comment by Flappy Bird on May 10, 2023 at 1:43 amWhether it’s to switch to a more secure platform, consolidate multiple accounts, or simply rebrand ourselves, the process of changing our email address can bring about both opportunities and challenges.

Comment by paper io on June 14, 2023 at 8:49 pmlayered some things on top of it. In the video, there’s a scene where I have a picnic and everybody there is a woman singer-songwriter, and every one of them has their own project. That’s kind of an intentional representation of the East Side of LA and the women who play music here.

Comment by jatin on June 18, 2023 at 12:19 amJusminh in to the app couldn’t connect to the right place. I hope apk website download official

Comment by DOWNLOAD INSTA PRO on August 20, 2023 at 8:40 amthis is an informative post and it is very beneficial and knowledgeable.

Comment by gorilla tag on August 21, 2023 at 2:32 amI hope you find this advice to be helpful. Please contact us if you require any additional assistance.

Comment by moto x3m on August 23, 2023 at 12:28 amPacman is a classic arcade game that has been around for over 30 years. It was first released in Japan on May 22, 1980, and quickly became one of the most popular games of all time. To celebrate its milestone anniversary, Pacman received an updated version called ” pacman 30th anniversary”.

Comment by Pacman 30th Anniversary on September 16, 2023 at 6:50 amNerdle is a popular online multiplayer game that pits players against each other in a race to answer trivia questions correctly. The game is fast-pace and requires quick thinking and reflexes. Today, we’re going to take a look at the differences between playing Nerdle on your computer and playing it on your mobile device.

Comment by Nerdlegame on September 16, 2023 at 8:35 amthe Dinosaur Game is a testament to the enduring popularity of classic, straightforward gameplay experiences.

Comment by zetisnoa on September 17, 2023 at 8:29 pmThe things you share are amazing and very helpful to everyone and me. Hope the best things will come to you, I have a small suggestion, you can play this game Run 3 to help you relax, it’s really fun,

Comment by Run 3 Run 3 on October 26, 2023 at 2:14 amThis is an amazing and informative article that covers so much ground.

Comment by slope on October 31, 2023 at 1:38 amYour knowledge is extremely helpful, and in my spare time, like you, I frequently look for games https://runaway3d.com/ to play to pass the time as an illustration, you might want to give it a shot at least once before deciding whether or not it’s right for you.

Comment by run 3 on November 13, 2023 at 5:14 pmThe Sportsfire APK download offers users a seamless live TV experience

Comment by monton roy on December 30, 2023 at 1:35 amenabling them to enjoy matches in real-time on the Krira TV Website platform without any lag.

Comment by monton roy on December 30, 2023 at 1:36 amI want to know your favorite music genre Suika game so I can recommend some good songs

Comment by rice purity test on December 30, 2023 at 7:37 pmMastering the art of sledding in this virtual winter wonderland promises hours of entertainment, making Snow Rider 3D a standout choice in the world of winter sports gaming.

Comment by Snow Rider 3D on January 1, 2024 at 11:44 pmi am seeing new dress for girls

Comment by ahsan khan on January 16, 2024 at 3:01 am