Culturally, we know and love them as partners in crime to the indie, alternative, and no wave/punk scenes, and for their versatility and flexibility that continually inspire sonic experiments that break the norms. Notable players who’ve recently been spotted repping their offsets include Molly Rankin of Alvvays, Alicia Bognanno of Bully, members of Warpaint and hundreds, maybe even thousands, of new players today. But, let’s get real: why exactly are offsets so desirable?

Let’s start with what makes an offset an offset in the first place. There are four major qualities that make up what we would consider a modern-day offset:

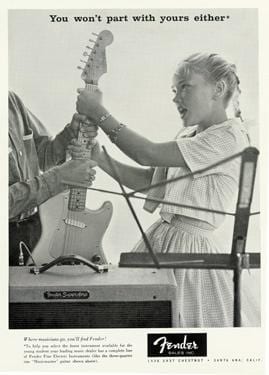

While you can look at any guitar with an asymmetrical body shape and call it an offset, the Fender Offset series evokes music and youth culture, and a movement that dates back to the late 1950s. In 1958, Fender introduced its first professional offset, the Jazzmaster. As you might guess from its name, the Jazzmaster was initially created with jazz musicians in mind—its asymmetrical contoured body shape was designed to make it more comfortable to play while seated than Fender’s classic Teles and Strats. An offset-bodied bass guitar, the Fender Jazz Bass, followed in 1960. But while Fender envisioned their new creations as high-end instruments for top-level players, the newfound versatility in the sounds they offered—specifically the Jazzmaster’s innovative tremolo system—instead captured the attention of a completely opposite type of musician; young, rowdy teenagers riding the wave of the emerging genre of surf rock.

Kathy Marshall performing with Eddie and the Showmen in 1964 with her custom Jaguar

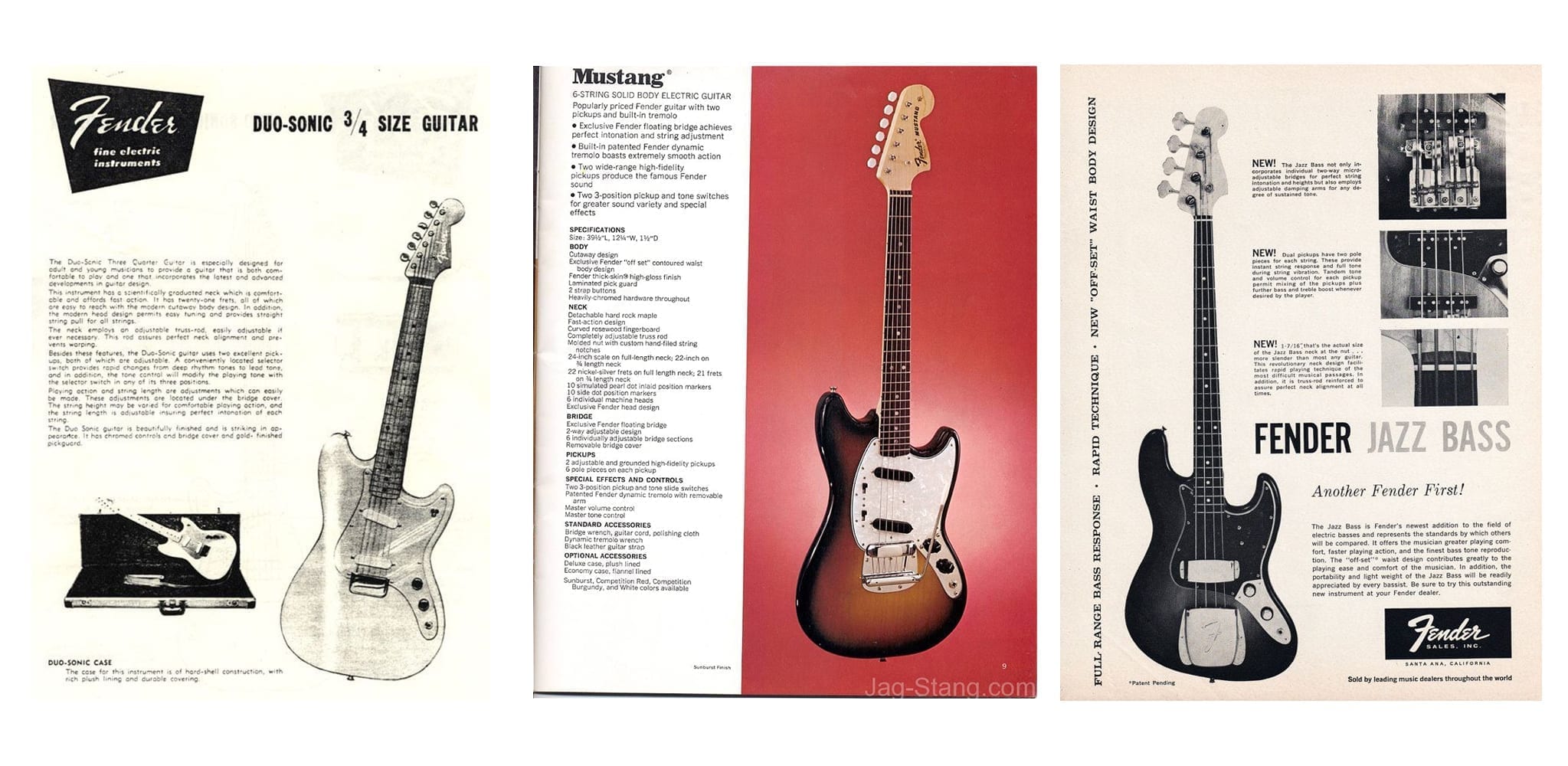

Kathy Marshall performing with Eddie and the Showmen in 1964 with her custom JaguarWhether it was its comfort, aesthetic, or tone—or a combination of all three—the wide success of the Jazzmaster among instrumental rock musicians and wavy surf communities created the desire for simple, affordable, and smaller-bodied options among a generation of new players. Prior to the Jazzmaster, Fender had introduced the Duo-Sonic, its first “student model” in 1956, offering beginner and young players small, lightweight guitars they could comfortably (and affordably) learn on, but it wasn’t until 1964 that the company unveiled the first offset in its student series: the Mustang.

While the Mustang’s body, weight, and neck scale resembled the earlier student model Duo-Sonic, its offset body and tremolo bridge system were modeled after the Jazzmaster—essentially taking the best of both worlds and making an inclusively versatile instrument. Shortly after, the two-pickup Duo-Sonic and single-pickup Musicmaster (another early student model) were upgraded with slightly bigger and offset bodies, and the company started offering them in small to medium-sized neck options. Following the success of these shorter scale guitars, Fender released what would be the last original bass designed by Leo Fender himself before the companies infamous shift to CBS—The Fender Mustang Bass. From there, the rest is history.

Due to changing music trends in the ’70s, Fender officially discontinued the instruments in the ’80s. But the versatile, inclusively designed offsets struck a chord with the burgeoning punk, new wave, and no wave scenes. Their sleek, simple design made them accessible to players who valued enthusiasm over expertise, and their quirky aesthetic made them a beacon for musical rebels and innovators while the smaller neck and body size offered an easy to carry, road ready instrument—praised by road dogs and bedroom players alike. And, importantly, these now-vintage instruments could be purchased relatively cheaply, secondhand. The identification of offsets with underground music stuck, and, bolstered by the rise of grunge, shoegaze, and indie-rock—and their adoption by icons such as Kurt Cobain, Liz Phair, and the Riot Grrrl Movement—Fender began reissuing offsets in the ’90s. They’ve remained a staple of independent music culture ever since.

One of the standout qualities of the 2017 offset series guitar and basses are their thick skin on the road. Although they are small, lightweight, and come in new high-end color finishes, don’t let their looks fool you—their bodies are nearly indestructible. The 2017 Fender offsets are offered with three pickup options—humbucker, single-coil or P90—a number of unique vintage-style colors, and a sturdier body design than ever. Plus, they are affordable, with prices starting at just over $500. They are a dream, and their popularity among indie musicians shows no sign of slowing down, particularly amongst women/non-binary and LGBTQ players. Erika M. Anderson of EMA, Chelsea Wolfe, Jessica Dobson of Deep Sea Diver, and Nik West are among the many musicians who have strummed their praises in conversation with She Shreds.

Check out our brief timeline of offset history for more dates, innovations, and pivotal moments you should know. You can find the specs and technical notes for each instrument model on the Fender site, but we’d rather use this space to pass the platform on to everyday offset users (randomly chosen from our #1RiffADay and the #FenderOffset on Instagram) to answer the question:

Name: Tilly Murphy (@fritzkid)

Playing For: 4 Years

Current Project: FRITZ

Current Set-Up: Olympic White Fender Mustang. Boss distortion pedal. Fender Frontman amp. Steinberg UR-12 Interface. Novation Launchkey Mini MIDI. Shure microphone.

“Sophie Hopes of the Perth band Tired Lion gifted me her Mustang at one of their shows in Sydney—said it was a way for her to encourage a new and upcoming artist like me, which I’m so grateful for. She even said something to me like, ‘Playing a different guitar to what you’re used to can bring you new song ideas,’ which is true because within the first few days of using it I had so many chords and new melodies in my head.”

Aesthetic. Having a good looking guitar is important!

Weight. I have no upper body strength and have no issue lugging my Mustang around with me, and the slightly shorter-scale neck makes playing easier, too.

Tone. I believe the tone of this guitar could work for every musician of every genre. (Plus if you’re anything like me, a HIGH priority is to give your Mustang a name. Mine’s Nana. Treat it like a child and it will last you a lifetime.)

Name: Jazmin Najera (@minutesfromjunesongs)

Playing for: 15 years

Current project: Minutes from June

Current setup: Fender Mustang 90. Fender Hot Rod Deluxe amp. Boss distortion. TC Electronic Ditto Looper. MXR reverb pedal. SM58 mic.

“I first saw the Mustang 90 at a local guitar shop and I was immediately drawn to the color. It was one of the most beautiful guitars I had ever seen. I tried it out and I was really impressed with the sound! I like playing garage rock kinda stuff, I’m big on distortion and overdrive, and the Mustang sounded great with my pedals, but I also appreciated the warm tone when I played it clean. And seeing artists I admire play Mustangs was definitely a selling point. I know Sadie Dupuis has the same guitar in white!”

Weight and Feel. The tone could be incredible, but if it doesn’t feel right and if it doesn’t feel comfortable in my hands, I won’t play it.

Tone. I looked for something that sounds great and offers me something I can’t get with the guitars I already have.

Aesthetic. My first choice, based on aesthetic alone, would’ve been the Shell Pink Mustang, but I wasn’t looking for single coils. Tone definitely takes priority over look!

Price Point. The price point is unbeatable—Mustangs are affordable. Overall, I think the new Fender offsets are fantastic guitars. I love the versatility and the range of sounds I can achieve.

Name: Intan Descenika (@intandescenika)

Playing for: 6 months

Current Project : Mery Celeste’s

Current set-up : Orange Fender Duo-Sonic. Hotone Blues Overdrive. Boss Chorus. Keeley Compressor. Hartke Guitar Amps. iRig 2 Amplitube. Pro Tools.

“It’s necessary in my band [to have a] kind of vintage tone—not really sharp or punchy but you can still feel the thick of the sound. Especially the single coil pickup makes the sound really great, clear, bright, and also warm and vintage sounding.”

Tone. It sounds like a mix between the Stratocaster and Telecaster. The offset gives me a perfect combination of both guitar sounds—a perfect new tone.

Price Point. It’s so worth it—a high quality pro guitar for about middle budget.

Aesthetic. It’s such a beautiful guitar, and it has a matte color and the Mustang shape, which I love. It’s not really huge on me, which is good. I choose Orange Capri because my band has a single titled “Orange,” so the color is meaningful to me.

Name: Raegan Labat

Playing For: 1 Year

Current Project: No current projects, but I was in a Devo cover band over the summer

Current Set-up: Capri Orange Fender Mustang PJ Bass. Acoustic B20 amp.

“Short scale, variety of pick-ups, and light weight seemed like the perfect first bass to own. There were a lot of bassists using Mustang and Jazz bass guitars, so it influenced to go Fender. Because I got the guitar when it was fairly new on the market, I didn’t see many people playing this model. Now, I’ve been to so many shows where the bassist is playing this offset model. It’s a little reassuring and inspiring—like when I saw Downtown Boys switch to this bass or when I saw The Babe Rainbow switch to this bass.”

Tone. I was new to bass when I jumped in and bought one, so I wanted something that I could trust sounded good and gave me versatility. I liked having the two pickups and being able to have the options to learn and discover which sounds I preferred through which pickups.

Aesthetic. It sounds silly but no basses felt like me. The offset series looks unique. The color was different. Its shape fit me really well and comfortably. They’re not vintage but you get something different with this model and that’s what I like (I definitely had the urge to go used and vintage). The short scale design felt comfortable enough that it actually made me approach learning to play bass with more confidence.

Price Point. It was a graduation gift and I’m a beginner, so the price point of this bass is such a sweet thing. You don’t have to spend much more than you would on other typical entry-level basses to get something of quality—and it’s an actual Fender model.

Weight. This was not something I thought about too much when I bought it, but I think subconsciously I loved it because it wasn’t heavy. There are some massive basses in this world. My friend plays a midnight blue Rickenbacker, and there’s not a chance I could play or hold that for an extended amount of time. The Mustang is great and doesn’t feel like it’ll float away, either.

1956: Fender introduces its first “student model” offset, the Duo-Sonic.

1958: Fender introduces its first professional offset, the Jazzmaster. The instrument was created as a solid body guitar for jazz guitarists, but it soon became enormously popular among rock musicians.

1960: Fender produces its first offset-bodied bass guitar. Like the Jazzmaster before it, the Jazz Bass was also designed for jazz players (particularly, upright bassists looking to electrify their sound) but also grew a following among rock musicians. A six-string offset bass, the Fender VI, was released the following year.

Early 1960s: Surf music springs off of California beaches into a national phenomenon. Due to their warm, clean tones and ease of playing at racing speeds, the Jazzmaster guitar and the Stratocaster guitar become the instruments of choice. The sounds from the whammy bar were thought to capture the vibe of ocean waves.

1962: Fender introduces the Jaguar, a new offset that featured stylish, space-agey chrome details. Built with an extra fret and a shorter scale (24”) than the Jazzmaster, it was designed to make playing even faster and easier.

1964: Offsets’ comfort factor and popularity with young musicians inspires Fender to create a short-scale model for student players, the Mustang. They also revamp the earlier student model guitars, the Duo-Sonic and Musicmaster, with new offset-style bodies.

1966: Why should guitar students have all the offset short scales? With a scale of 30” and offset body, Fender’s Mustang bass becomes the company’s first-ever student bass guitar.

1975: Due to changing music trends and declining sales, Fender begins to discontinue its offset models, finally halting production on the Mustang in 1982.

1975-1977: Youth culture once again has a surprise in store for the guitar industry; as punk emerges on both sides of the Atlantic, offsets’ ubiquity, ease of playing—and the fact that they could be found cheap—makes them a hit with a new set of musical rebels.

1980s: Fender Japan is opened for business, and launches a number of offset reissues as part of it’s instrument line.

Early-mid 1980s: Punk births new wave, post-punk, shoegaze, and other subgenres where individualism and experimentation are prized more than perfection. During the same period, there is a renewed interest in garage rock and surf music. Offsets become a gear cornerstone for yet another generation!

1990s: In response to the growing love of vintage instruments among grunge and alternative guitarists, Fender officially relaunches its offset models with updates to correct many of the perceived flaws of the original versions.

1992: In an interview with Guitar World Kurt Cobain names the Mustang as his favorite guitar in the world, listing its small size, price point, and its quirks and imperfections as his reasons for loving it.

1997: Courtney Love launches a new offset, the Squier Venus (or Fender Vista Venus), making her the second woman to have a signature line from Fender after Bonnie Raitt.

2003: Liz Phair poses with her trusty Duo-Sonic on the cover of her self-titled album.

2010s: Offsets continue to thrive in the indie music community. Their versatility and comfort makes them a perfect fit for a variety of music styles and players. They provide a dependable, cost-efficient staple for musicians who are more likely to buy a bunch of pedals than “trade up” for a more expensive guitar.

2016: Fender releases its Offset Series, featuring new models of Mustangs and Duo-Sonics. The instruments come in a variety of finishes; the Mustang comes in Arctic White, Capri Orange, and Torino Red, while the Duo-Sonic HS comes in Daphne Blue, Black, and Surf Green.

2017: The Fender Offset series releases a new set of vintage inspired colors for its revamped Mustang, Mustang90, Mustang Bass PJ and Duo-Sonic models including capri orange, surf green, shell pink, daphne blue, and canary diamond.

But it was a dream come true for Le Butcherettes frontwoman Teri Gender Bender. As her newly formed alt-cool supergroup Crystal Fairy was writing and recording its self-titled debut in El Paso Texas, Teri’s mom cooked chilaquiles for the band. They then watched Ravenous, a cannibal/dark comedy Osbourne brought along.

But it was another film that inspired the band name (and song). “We’d watched Crystal Fairy [& the Magical Cactus] with Michael Sera and Gaby Hoffman, done by a great Chilean director [Sebastián Silva],” Teri explains. “Then, in the studio, all our writing was real-time and improvised, so when I sang “my name is Crystal Fairy,” Dale just started laughing, like, a genuine ‘this is cool.’”

Almost as cool as Teri herself. Born Teresa Suárez Cosío, she’s lived in both Mexico and the U.S., and is conversant about both Presidents Trump and Enrique Peña Nieto. She’s well-read (citing Sylvia Plath and Portuguese poet/writer Fernando Pessoa) and, while she’s a feminist artist who has been inspired by human tragedy, she says, “nowadays more than ever I’m trying to be inspired by human kindness, which can be hard to find nowadays.” We chatted with the singer/guitarist whose formidable talent is matched only by her humble likability and thoughtful demeanor.

Crystal Fairy’s self-titled debut album is available now through Ipecac Recordings.

She Shreds: The seeds for Crystal Fairy (rounded out by Mars Volta/At The Drive-In’s Omar Rodriguez-Lopez), were sown when Le Butcherettes opened for the Melvins. Had you met the band previously?

Teri Gender Bender: No. I opened up a show for Jello Biafra, so Buzz showed up early to support his friend, and he saw our set. Small fricken’ world, we have the same booking agent [Robby Fraser at William Morris Endeavor], so he told Robby, “I’d like the Butcherettes on the tour.” Robby told me “Buzz never does this.” It was very kind of him; he didn’t have a reason to invite us on tour, much less give him the time of day on tour. On tour, they would help us load out and load in. You never get that kind of treatment in the normal world, much less the touring world.

As a kid, what was your first instrument?

I grew up listening to the Dead Kennedys, Bikini Kill, L7. My mom is a big Turkish pop fan; we had a lot of that in the house. [Jello’s] words opened up a lot of portals of interest into poetry, surrealism and politics for me. There’s a lot of angst here, I can relate. I play keyboards and guitar, but I started guitar when I was 12. The reason I picked it up. I kept having a nightmare that I was playing an acoustic guitar, but every time I’d try to strum the strings, they would melt. That horrible feeling of not being satisfied. So I’d wake up angry. So I’d take rubber bands, stretch them out and pluck them to get my anxiety out. Then with my lunch money—my mom wouldn’t let me work, because she was protective—I saved up to buy a guitar.

Being able to strum those strings was another spiritual experience, dare I say a religious experience. I remember the first time I broke a string: I didn’t know you could replace them. I was like, “oh, I just fucked up my guitar.” I cried so much. Until I found out I could replace it.

Tell me about the writing for the Crystal Fairy album.

It was super easy going. Our definition of having a party is locking ourselves in a studio and making music and jamming out. And the cherry on top is a little coffee break in-between! We all wrote. It was great to see the magic happen in front of me. Those moments when Buzz looks at Dale and they kind of giggle like “yes, we have this!” And they can read each other’s body language. Omar is a great bass player, it was interesting to feel these people I admire so much working so well together. And giving me the freedom to work with them. Not one person was telling me, “oh, no, your lyric is dumb.” Which is good, because I’m already my own worst enemy. It was, “We’re all pretty much equal here, this is fucking awesome.” Excuse my language.

It was such a euphoric moment. Because when I started my band in Mexico, it was a constant uphill battle, going against these sexist remarks, a lot of insults: “This whore just wants attention.” “Oh, she only plays two chords, of course she’s doing well because she probably fucks the men who help her out.” Horrible things. I felt like my heart was healing when I could see my work pay off, people I listened to as a little girl [supported me]. A very spiritual moment for me. Of course, there are people who supported me from day one. But overall, it was a constant uphill battle.

You sing one song, “Secret Agent Rat,” in Spanish….

That came out of nowhere. The funny thing is, while I was doing it, it was like “record a take,” then I said, “let’s do it again,” so quickly I counted the syllables in English and tried to make it fit into Spanish. I did the song in Spanish, and at the end of the take, Buzz was like, “that was weird, really crazy and creepy.” I was like “what?” He said, “I was just about to suggest you sing that in Spanish!”

Growing up, it was 100 percent Spanish in the household. I lived in Denver due to [my] father’s job. And my school 100 percent English. When my dad died, we went back to Guadalajara [Mexico]. Again 100 percent Spanish. Interesting cultural clashes. In the States I never felt like I belonged, because I had an accent. In Mexico, it was like, “you’re like a Gringa, a white woman.” It’s very classist there. Even if you’re Mexican, but have a lighter shade of skin, there’s that type of racism. My mother’s Mexican and my dad was Spanish. It was, “Oh, of course, you have Spanish blood, your men raped our women and girls.” There’s still very much of that ingrained.

Buzz’s guitar sound is legendary and loud. How did your guitar playing change for Crystal Fairy compared to Le Butcherettes?

I’m a very limited guitar player. I made my own way of being able to play. I only play with four strings. It was a slow process, because at first I only played with one string until I got my fingers used to that one string, then I added the second string. And I was able to dominate the second one. Eventually I got to the fourth string, and all my fingers are now preoccupied. So I tune it E C E G sharp, kinda like a banjo tuning, maybe. The way I press it down makes it sound like a chord.

No matter what movement I made on the frets, it sounds pleasing to the ear. This is just in my own ear. I should have gone to [music school]. So when I confessed this to Buzz and showed him what I do, he was like, “cool.” I showed him the song called “Sweet Self,” the chords which was originally a Butcherettes song, and he said, “sweet, keep it like that.” We both played around and added a bridge, and when we finished the rehearsals, he got me a Danelectro, gold colored. That was really sweet. He gave it for me to use for the Crystal Fair entity, but before I’d always play the Squier Jaguar, salmon colored. This is the first interview where I’ve talked about the guitar I play; this is awesome! I’m actually being considered a guitarist! Damn it, I made it work somehow. [The way I play] is super-easy, so I’m sure I could teach someone in five minutes. I’m a cheat guitarist.

Teri Gender Bender’s tuning and finger position for bar chords. Illustration by Frances Kinas

Teri Gender Bender’s tuning and finger position for bar chords. Illustration by Frances KinasWhy didn’t you take lessons?

Money was always an issue. Later on, I was stubborn, so I’d go on YouTube, when I was in Guadalajara. And I don’t know if it’s ADD or I’m too much of a rebel, but I couldn’t pick it up. So I got one of those TAB books. It just didn’t feel natural to me. Now that I’m surrounded by guitarists, like Omar is showing me how to warm up my fingers, while using all the strings, an exercise. Ironically enough, one of the first people to try to give me lessons was a drummer, [Gabe Serbian from The Locust, Cattle Decapitation]. I can play standard guitar a little bit. I want to continue, definitely, I want to get better at all guitar craft. The reason I kept going on with my cheat was that it allowed me to make punk music—anything’s allowed in punk.

So given your low-fi, DIY approach you must use a cracker box for an amp?

Ha! I use a cereal box! Actually, before when I started playing Guadalajara, I’d go straight to the amp. The money issue thing. I was proud, I didn’t want to ask for favors; “oh, lend me your shit.” I didn’t even have my own amps back then. I’d use anything. Show up and plug in. Eventually, Orange was able to cut me a deal. I have an Orange Crush Pro 240. The head for the amp is called Verellen – Skyhammer, by this great boutique company in Seattle. I get this crunchy tone without overdoing it on the distortion. When our front of house/guitar tech guy can’t come on tour, I’m my own guitar tech; if for some reason the jack is screwed up, or whatever, I take my little tweezers and try to fix it. Gotta make it work until the wheels fall off!

You’ve lived in both Mexico and the U.S. I can’t imagine how you’re feeling about President Trump and his policies.

Obviously, I’m completely against the wall, but I’m not going to hate someone who is for it. I’m going to listen to their point. I’m pro-information. On a symbolic level, what’s going on, with the wall, it’s horrible, but at the same time, there are always two sides. And this is coming from a Mexican-Latina feminist! Guatemalans cross to Mexico, the Mexicans have no sympathy; the Mexicans use machetes on the immigrants from Guatemalans who try to get into our country, chopping them into pieces.

The New York band’s 1963 deal with Decca came at a time when women in popular music were predominantly vocalists accompanied by male musicians or, such as in the case of legendary session bassist Carol Kaye, relegated to behind-the-scenes roles. Today, the Gingerbreads’ legacy extends beyond an answer to an obscure trivia question in part because it propelled guitarist Carol MacDonald to a lengthy run as a creative force and LGBT voice in mainstream rock.

Goldie and the Gingerbreads was formed in 1962 by band namesakes Genya “Goldie” Ravan (vocals) and Ginger Bianco (drums). Organist Margo Lewis swiftly replaced original member Carol O’Grady, and after a year-long search for a guitarist, the lineup became complete when MacDonald joined the fold. While there’s little information available about MacDonald’s pre-Gingerbreads career, it’s unlikely her bandmates’ lengthy search ended for a novice performer. In fact, her skill with a Fender Stratocaster solidified the group’s formidable take on the then-popular Mersey beat sound.

The band’s groundbreaking career lasted five years and produced a handful of 45s, including a 1965 cover of Herman’s Hermits’ hit “Can’t You Hear My Heartbeat” that cracked the Top 25 in the United Kingdom. Other standout tracks include organ-driven garage stomper “The Skip” and “Sailor Boy,” a doe-eyed love song with girl group style vocal harmonies. The band performed these songs in the states and overseas, sharing stages with rock ‘n’ roll peers such as the Rolling Stones, the Animals, and Chubby Checker.

After the Gingerbreads parted ways, MacDonald (vocals, guitar) and Bianco (drums) formed the all-woman horn-rock ensemble Isis in 1972. Lewis joined as organist and keyboardist a few years later. The critically-acclaimed band mirrored the sound of the times, adding their own spin to funk, jazz fusion, and blues-rock.

Isis became only the fifth all-woman band with major label backing after signing with Buddah Records in 1973. This lack of all-woman bands acknowledged by the mainstream, just a few years after the counterculture’s spirit of protest radicalized facets of popular culture, casts the music business of the early 70s as severely behind the times.

During her years with Isis, MacDonald became openly gay, broaching the topic as a songwriter with the tender-hearted “She Loves Me” and fiery freedom anthem “Bobbie and Maria.” While it’s encouraging to know that such songs were released back then by a major label, MacDonald later told She’s a Rebel: The History of Women in Rock & Roll author Gillian G. Gaar that coming out of the closet was discouraged within the music business and likely halted Isis’ shot at commercial success. Despite a lack of hits, the band maintained a visible platform as a touring act, sharing stages with KISS, ZZ Top, and Lynyrd Skynyrd.

Interest in Goldie and the Gingerbread’s legacy has spiked at times over the past 20 years, including a one-off comeback show in 1997 and inclusion in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s 2011 “Women Who Rock” traveling exhibit. An Isis reunion followed in 2001 but was halted by MacDonald’s health concerns. She passed away in 2007.

Each flurry of interest in MacDonald’s career draws well-deserved attention to two of the first all-woman bands signed by major labels. It also highlights the varied contributions of a guitarist, singer, and songwriter whose brilliance outshone cultural biases against her gender and sexuality.

In 1956, while looking for a means to support her family as a teenager, Abigail Ybarra walked into what was then a small 10-year-old factory called the Fender Electric Instrument Company. Fifty-six years later she would be coined the “Queen of Tone” for her handcrafted pickups, and considered a true staple of Fender’s legacy around the world.

While Ybarra’s story is without a doubt monumental on its own, it turns out she comes from a lineage of Latina pickup winders who were prominent during a time when the Fender company sought out women to work on the guitars. First there was Pilar Lopez (whom Ybarra apprenticed under), followed by Abigail Ybarra, and today—after three years of learning from Ybarra herself—Josefina Campos continues what we can seemingly consider a tradition.

Now, after retiring in 2013 at 80 years old, Ybarra resides in Redmond, CA where she continues to dabble in pickup winding. She Shreds had the honor of speaking with Ybarra on the phone to discuss some Fender history, beginning her own operation, and winding enough pickups to wrap wire 16 times around the globe.

She Shreds: How did you first get in touch with Fender?

Abigail Ybarra: Yeah, that’s a story right there. My cousin Corin used to work for Fender and she quit so then—maybe a couple of years later—she was looking for a job, so I decided to go with her, and for some reason they hired me but they didn’t hire her back. When I walked in the office I was given an application and right then and there they took me to the back and I was hired.

You said that your cousin used to work for Fender. What did she do?

She used to solder. She used to do some of the wiring and controls on the pickguards and guitars. That is actually what I started doing—and by the way, I was told that I was going to get 90 cents an hour and that in 30 to 60 days I would get another dime, and I thought that was great.

What did your parents do for work?

My father had died, and it was just my mother and two sisters. So, this was a job. I found out there was a place I liked being a Latina, and the pay was pretty good. It was a time [when] we had an incentive plan and we were earning more money in Fender than in other companies around there. I remember there was this girl that came in working in the office—when she saw our checks, she transferred into the factory.

So, you learned the back end of guitar building in general and not just pickup winding, even though that’s what you are known for.

That was where I ended up somehow over the years, when CBS bought the company from Leo Fender. They pretty much did not let people transfer up and down from one department to another, and there was not that many people who wanted to wind pickups all the time. But I always liked that—for some reason I was comfortable doing that, so I just stayed working on pickups.

What do you think it was about pickup winding they didn’t want to do?

Most of the girls would just say it was boring. I mean, you sit there and you wind. We did not do hand-winding for a long time . . . once CBS took over we got automatic coil winders, so even then the girls didn’t like running the coil winders. They had a lot of problems with wire breaking and somehow I just kind of took to it because I didn’t have that much trouble. So, for many years we did not do hand-winding until I came over here to Corona, California and they wanted me to do hand-winding pickups again.

It sounds like there were a lot of women in the factory. Why was Fender looking for women to work on pickup winding?

They figured that men’s hands were too rough, men just wouldn’t be able to handle such delicate work, so it was just women.

You retired in 2013. Is there a big difference between winding pickups in the ‘60s and in your last years at Fender? As the guitars evolved, how did the pickup winding evolve as well?

Well, by the time I retired I was doing hand winding again. When I started in pickups with Leo Fender, back in Fullerton, we were all doing hand-winding. He asked for and usually got superior work. I don’t want to say—I think it was better back then. Of course when I started doing hand-winding over here in the custom shop I tried to do what Leo Fender had expected us to do back then.

And what was that?

Perfect work. Really serious about what we were doing, taking pride in what we were doing—that’s what he always said. We were part of a great company. Leo always thought that we were the Cadillac of guitar making—in those days Cadillac was the best. So when I came over here to do hand-winding again in Corona, I tried to do the same thing. I was much more of an expert at winding, giving customers what they wanted.

Do you miss being in the shop every day and winding pickups?

I do. I miss the people. I miss the fact that we used to get reporters to come in here and talk to me. It was a fun place to be, I do miss that.

Was there any particular reason why you felt it was time to stop?

Not that I didn’t feel that I could still keep working, but it used to bother me that some people used to come up to me and say, “You’re what? You’re in your 70s and you’re still working? You should be at home.” And I thought maybe they’re right, here I am going on 80 years old and still working.

I feel like that’s what keeps us all alive, is to do what we love, right?

Right? Sometimes I regret that I’m not still there, still going to the NAMM shows.

What do you spend your days doing other than pickup winding?

Nothing, nothing! That’s why I’m telling myself I need to start working, I need to start my own thing, my own pickup.

When Josefina started her apprenticeship with you, what did you make sure to emphasize in the learning process for her?

I trained her exactly the way I was trained back then. I was trained by a girl that Leo Fender trained, and she is the one that trained me. Her name was Pilar Lopez. So when I trained Josefina, [I trained] her exactly the way my work ethic [is], I tried to pass that on to her.

Can you tell me a little bit of what that includes? Is your work ethic based on being authentic and committed to the work or is there something specific, technically?

I taught her, or tried to teach her, to do the job the way I learned to do it—even the soldering. I like to do that with a good pickup that’s gonna last for years. Working in a mass production, I really don’t think that those pickups are that great—seems to me that she needs to take the time to do the job right, not to think about how fast she is going to do it but what a good job she has to put out.

Is it important for you to inspire and encourage other girls to be a part of this kind of work?

My daughter is going to start working with me because eventually I plan to start my own business. I would encourage girls to do that.

How many pickups do you think you’ve wound? Per day or per week?

Leo never had us winding for eight hours. He would only have us do it for four hours because he thought for us to sit there for eight hours was too much. So in four hours we would do something like 15 or 16 pickups. With CBS it was different, we had automatic coil winders, we turned out hundreds on the coil winders. Hand-winding, you can’t wind too many—it’s a slower process.

We had people from Made In America come down to the plant in Corona—it’s a show on Discovery [Channel]. The one guy that was on the show figured out that I had wound wire—just the wire— around the world 16 times.

That’s an amazing fact.

That was so weird. Time just flew . . . by the time I was finished I could not believe it had been that many years. I guess time flies when you are having fun.

Belvedere by DiPinto Guitars

The Belvedere is a great example of an instrument that plays with a smooth, distinct energy, while simultaneously being an incredibly attractive object. It is a modern guitar with a vintage soul. I have been to the DiPinto Guitars’ storefront in Philly and I had a great experience. They are unpretentious, approachable, and unafraid to try new designs. -Leah Wellbaum / Slothrust

Chris Letchford CL7 Signature Multiscale Headless Guitar by Kiesel Guitars

These guitars are definitely super high quality in every aspect. The materials, the construction and the feeling are on the highest level. The quality of the sound and the electronics is great, super sensitive, and very diverse depending on the players need. Also, they can make custom guitars with a lot of different choices for any type of player of any genre. -Laura Klinkert

Oyster Orbit by Malinoski Guitar

The Oyster Orbit by Malinoski Guitar looks like a beautiful muppet creature. Its unusual shape is a bit intimidating, but its fake fur is quite soft. This thing feels alive. If it was wasn’t inappropriate, I would have put my face on this guitar. I favor it as a piece of art as opposed to a practical live guitar choice but, if I saw someone playing one, I would definitely be winking at them all night. -LW

Raven Superbird by Tom Anderson

I have been looking for a guitar like the Raven Superbird by Tom Anderson for the past year. It has a body shape very similar to a Jazzmaster and contains the same tremolo system. However, unlike the Jazzmaster, it is incredibly light. This is a perfect alternative for someone who is attached to their Jazzmaster but wants something that weighs significantly less. It also stays in tune and can do bends up to 5 frets. You will be able to play the guitar solo in “Bohemian Rhapsody” with no problem. Sick. -LW

Relish Guitars

Relish guitars are made in Switzerland and feature a revolutionary construction. All of the components of the guitar are mounted to an aluminum frame. The magnetic back of the guitar pops off to expose all of the electronics making everything completely accessible. The neck is bolted on and sports a beautiful bamboo fingerboard. It is obvious that the details on this guitar are meticulously thought out; it plays and sounds like a dream! –Laurence Vidal

Mike Watt “Wattplower” Signature Bass by Reverend Guitars

Out of all the booths I visited at NAMM, Reverend Guitars’ booth is still forefront in my memory. The Wattplower, the new Mike Watt short-scale, signature bass, particularly caught my attention. Available in satin powder yellow or satin emerald green, this bass has a certain understated elegance. Small embellishments such as the anchor inlay on the first fret and a seventeenth fret marker that says “Wattplower” really give this bass a unique aesthetic. It is equipped with Reverend Guitars custom P-blade pickups that give you a classic P-bass sound with added sustain and low end response. Pick one of these up for $1,399. -LV

The professional-grade instrument series, which will debut at the NAMM conference on January 19, updates the sounds and style of Fender’s classics with modern features including a new neck profile, pickups, tuners, additional colors, and more.

The American Professional Series also adds a new Jazzmaster and new Jaguar to the Fender collection. Check out the full selection of instruments, and a video preview of the Professional Jazz Bass featuring Nik West, below:

For more information on the Fender American Professional Series, check out a Fender dealer near you, or if you’re able to, head over to NAMM next week!

“[With] bands I’ve been in, people are sometimes like ‘oh that’s cool, sounds like this particular area of music,’” she says. “It’s that linear kind of mindset, ‘this was a particular era, the golden era of music, and everything else that came after that is just derivative’ and it’s like, no, we’re not trying to be some 70s worship band, we are continuing a really beautiful tradition. That’s how I like to see it, you know, this is a tradition and everybody adds different things every generation.”

Barkley has been playing guitar for twenty years. She grew up in snowy Buffalo, NY and started playing guitar as a teenager. Influenced heavily by rock ‘n’ roll, blues, West African psych and 1970s Japanese progressive rock, she is a relentless songwriting force. When we met over a decade ago, it was summertime in Philadelphia, and I was just getting to know just how vast queer punk underground music was at the time. I happened to be in attendance at what was one of Purple Rhinestone Eagle’s first shows and, as a teenager, I remember watching them play and being inspired to continue playing my own music.

Barkley has diligently honed her craft between finishing grade school and being mentored by the likes of violinist India Cooke. She is insistent on following the lead of guitarists who, as she puts it, “don’t take up more space with the guitar than they should musically.” It is a fine balancing act to play with such intention, it’s all about the intimate relationship of guitar technique and songwriting that really sets her music apart. Both of these are paramount to, and have grown together harmoniously, in her music.

Under the name Dre Genevieve, Barkley is planning a 2017 tape release on Eye Vybe Records, a solo EP titled “Strangely Free.” Gratitude, presence of mind, and the finite quality of life are running themes within these songs. “Music is definitely something that has allowed me to transcend any sort of hurtful thing that I might do to myself, spiritually or mentally.” Barkley says.“[Guitar] just feels so good to play, it feels good to connect with that particular instrument.”

It’s appropriate to link her guitar playing to a lineage; a shared experience that Barkley says “transcends time and space” and builds onto itself. Within this large family, women, queer folks, and people of color have built pathways for players who seek to come after. For Barkley, paying homage to these trailblazers is important both in the evolution of guitar and in her songwriting. Beverly Guitar Watkins, Odetta, Selda, Albert King, Hideki Ishima, and Nancy Wilson are just some names that breathe life to her musical palette. “I love all of these people, not only for their respective guitar prowess but also they were/are all incredibly gifted songwriters. You can hear it in their music. They all think outside the box. They don’t wank off.” she says.

In regards to being a queer woman of color musician, she says, “when you are on stage and you’re owning it, when you’re unapologetic, it’s like you are really blowing people’s reality tunnels wide open. We just gotta keep doing it.”

Barkley recently spoke to She Shreds about “Strangely Free.” 100% of download proceeds will go to aiding the victims of the Ghost Ship warehouse fire on December 9th, 2016.

She Shreds: Growing up, did anyone play music around you? Were there any big influences in your young life?

Andrea Genevieve Barkley: I had an older cousin growing up who was a total hesher who would babysit us when I was about five or six. She’d bring over her metal and rock cassette tapes stuff like Lita Ford or Metallica. She’d play them really loud on my mom’s boombox and my brother and I would tear through the house screaming with delight. I would sometimes pick up a broom and start playing it like a guitar. I guess she has some pictures of me somewhere doing that. Musically my cousin was a big influence on me. She listened to all kinds of music and would tell me to check out this or that band as I got older. Once I started playing guitar for real she got really stoked for me. She’s been one of my biggest supporters my whole life.

Would you say the music you play is mostly in the veins of psych and progressive?

Yes definitely. Psych and progressive for sure. Specifically I think I draw from 70s West African psych and 70s Japanese prog. And I pull a lot of inspiration from late 60s blues. I love a lot of early krautrock bands like Amon Düül II. I also love certain acid folk stuff too, Turkish stuff like Selda and British and Welsh stuff like Forest and Bran. I think all of that influences my playing. I’m also super into early experimental synth stuff like Terry Reid. A Rainbow in Curved Air is one of my absolute favorite albums. No guitar in it as far as I can tell but lately it’s been influencing my writing and playing a lot. It’s so otherworldly.

What would you say are your main motivations for playing music and more specifically, refining your guitar craft?

I’m not sure what motivates me to play guitar. I absolutely love songwriting and performing. It’s just the most fun in the world to me. Maybe that’s it. I love learning new scales and techniques. I’m constantly teaching myself new things on it. I’ll listen to someone else’s song and I’ll be like “how the hell did they do that?” and noodle around until I figure it out. Lately, I’ve been playing a lot of piano, recorder, melodica and bass, too, but I always come back to guitar. It’s such a fun instrument. There’s always something new to learn. Having “beginner’s mind” and staying curious is my approach. It never gets old that way.

Being a queer woman of color, it’s important for me to keep doing what I do so I can help to dismantle the idea that rock n roll only doesn’t “belong” to people like me. I’m Black so in actuality, my people invented rock ‘n’ roll. The more of us out there doing our thing, the more we can chip away at these antiquated ideas. I want to do what I can to inspire other women, girls, queer folks, and whomever else to start playing music if they feel the calling. And for my male contemporaries, I’m doing this for you too. Maybe my presence will help to check your internalized misogyny that you have been socialized to believe.

Not to say all musicians are marginalized but, in a way, if you just look at, unfortunately, [the Ghost Ship warehouse fire], some communities of artists are marginalized. Speaking of queerness and any person who is on the outside, you have to find your family. I’ve always been obsessed with rock ‘n’ roll and, of course, the dominant culture wants to portray that as only these particular men, from these particular countries, and this particular background are values and important. I just never believed that to be true.

“Strangely Free” cover art

“Strangely Free” cover artWhat is the meaning behind the title “Strangely Free?”

I named the EP “Strangely Free” because I have been letting go of so much in my life these past few years. Things that I used to be able to count on are no longer there. After going through an intense period of mourning, I realized that my deep internal happiness is not contingent on anything, any band, or any person outside of me. In that moment I feel really bizarrely free, like I could do anything because I could! Taking this to the larger social context, I believe that most of us can still find a lot happiness despite the fact that large social systems are totally breaking down as we speak. In fact it may actually be a good thing this is happening. We don’t know what the future holds so we really need to embrace now – right now – and do the things that make us happy. Speak our truths. Stand up. Get our lives. That’s the sentiment I wanted to express in this album. Don’t waste a moment.

Would you say music and your spirituality can be connected? And how would you define your spirituality?

Songs can travel. Music is probably the oldest form of artist human expression. Scientists have found instruments that are hundreds of thousands of years old. So when we play music, we are connecting to something very ancient within ourselves. I think when we play music with that sense of connection, it starts to dissolve fears, loneliness and whatever other harmful thoughts we may have. It gives us renewed purpose and reminds us of how extraordinary life can truly be.

In terms my own spirituality, I consider myself to be Buddhist. I’m a part of a really wonderful sangha in Oakland called the East Bay Meditation Center. With Buddhism, it’s more about the practice and less about holding this identity, so it often feels kind of strange to say “I’m a Buddhist” But being a Buddhist has really shifted my worldview. Approaching music making with loving kindness as opposed to ego makes for better songwriting and performance too.

Throughout the years you all have been asking us to suggest gear that we can’t live without. That, paired with so many new and improved tools that came out in 2016, made us realize that we needed to add a fourth release to our year. Unlike the rest of our print publications, The Guide will be a 100% free of charge bonus issue sent to She Shreds subscribers and available digitally to all. Written by locally respected and loved guitarists (full list below), the Guide includes artists from past issues and their gear as well as picks for the categories of Guitars (electric, acoustic and bass), Amps, Pedals, Accessories and Vintage; all of which are directed to pages that will provide more information on the product and purchasing options. Check it out below and happy shredding to all y’all shredders out there!

Designed by Eileen Tjan of Other Studio, The Guide features reviews by:

Miss Alex White (White Mystery)

Amanda Glasser (Purrer)

Claudia Meza (Explode Into Colors)

Devin Trainer (Club Night)

Glenn Van Dyke (BOYTOY)

Lance Seymour (Gear Talk)

Laurence Vidal (Tiburones)

Lena Simon (La Luz)

Randy Randal (No Age)

And She Shreds Founder and Editor-in-Chief Fabi Reyna

Thanks so much to Guitar Center, PRS Guitars and Ear Trumpet Lab for the

If you’d like to receieve a physical copy of The Guide, free or charge, please fill out the submission form below!

*USA only

Though many musicians have a natural knack for differentiating and connecting sounds and rhythms, developing listening skills through ear training can help anyone become better at their craft, regardless of prior formal training or experience level.

“Ear training is the practice of listening closely in order to identify different aspects of music like pitch, intervals, bass lines, melodies, chords and musical qualities like rhythm, timbre and tone,” says Nashville-based experimental pop/folk artist Ariel Bui. An accomplished musician who formally trained in piano and piano pedagogy, Bui began teaching herself guitar as a teenager, and has been playing ever since. In 2012, the Nashville-based artist founded Melodia Studio, where she teaches lessons to students of all ages.

We recently asked Bui to chime in on how ear training can positively impact guitarists and bassists and some tips for musicians of any level to improve their skills:

Why ear train?

Musicianship… By developing keen listening skills, you can learn what it is you like about your favorite songs so that you can develop your own voice and your own style. Ear training is essential to musicianship, whether it be while playing guitar, performing, or songwriting. Music is an art form that relies on the essential act of listening, so when creating or performing music the ultimate goal is to be able to replicate, execute, or create sounds intentionally, expressively, and musically for yourself and others to listen to.

Guitar playing… I taught myself how to play guitar by ear, so ear training impacted my guitar playing in a huge way. Ear training allowed me to learn guitar parts, picking patterns, strumming patterns, chord progression structures.

Songwriting… My ear training has affected my songwriting because I listen to the way songs move from section to section, how many times each section repeats, how and when they change, when main musical ideas return, how the tonal center moves and modulates, and more.

Performance… Learning to critically and objectively listen to yourself comes with time, and once you develop the ability to hear yourself and/or your band, the better you will be able to confidently perform live or in the studio, especially in situations where you can’t really hear yourself on stage that well, or when you are under pressure and nervous. Also, the ability to critically listen to your favorite performances allows you to learn and draw inspiration for how you would like to improve your own style.

Ear Training Tips and Exercises:

Learn Covers: Learning covers is my favorite way of improving my skills. It isn’t until you try to replicate something that you will catch details about the music you probably would not have realized without actually trying to play it. I teach myself songs by using a combination of tablature and learning by ear… Even when using tabs, I will defer to my ear, taking the tabs as a suggestion and figuring out if there’s a more comfortable chord placement, or any wrong notes or rhythms. Learning covers by ear is how I learned to play guitar and essentially how to write songs.

Start Simple: I would recommend starting out by listening to songs that don’t have a lot of other instrumentation on them to be able to hear your instrument of choice more easily. I started out with songs like Led Zeppelin’s “Babe, I’m Gonna Leave You” that have just guitar and singing at the beginning.

Find main pitches and melodic lines: From there I would listen for a distinct line, usually a bass line or sometimes a melody, and try to figure out the starting note or pitch. If the bass line or melodic line has too many notes, I will just listen to the first few seconds or minutes of the song to hear what note seems to be recurring and sticking in my head the most. This usually ends up being the key or scale that the song is in. Try to find it on your instrument. From there, it can be like playing a game of Simon Says. The first note is this, the second is that. Okay what’s next?

Keyboards and pianos are handy: If you are having trouble with identifying pitch, keyboards and pianos are always handy to have around because they should hopefully be in tune and can be a less cumbersome tool to feel around with for matching pitches. At a piano, you don’t have to worry as much about your guitar technique which can be especially challenging for beginner guitarists.I would highly recommend doing something as simple as quizzing yourself with pitches, listening to a tone and seeing if you can match it. If figuring out melodies or bass lines is difficult, I would also practice being able to identify when notes are moving up or down in the scale, or in other words, being able to hear if the notes are moving higher or lower, and eventually what the intervallic distances are between the notes.

Listen for different voicing within chords: First, I’ll try to follow the bass line (and if you are playing the guitar, remember, guitars have their own bass lines, too). I played a lot of finger picking music to start off with, with folk music or classical guitar music performed by Andres Segovia, so it was important I isolate the thumb’s picking patterns before trying to add in all the other notes.

After identifying the bass line of the guitar part, you can start isolating perhaps a middle line (similar to an alto line in a choir) and then a higher melodic line. By listening over and over, I usually will isolate one line within the guitar chords at a time, to hear the melodic and chordal qualities of the song. It’s also helpful to listen for open strings (more resonant sounding) versus strings that are fretted, so you can figure out a chord’s placement on the fretboard.

Listen for chord quality: You will eventually want to not only listen for the specific notes within a chord but for the chord quality. Does it sound like a major chord (often described as happy sounding), minor (described as sad sounding), or something else like a 7-chord, augmented, diminished, etc.

Get Rhythm: When it comes to strumming chords, it’s also good to be able to listen for strumming rhythms and patterns. Does it sound like a series of strumming down? Or does it go down-down-up-down? Do you strum all the strings or only some? Do you do a combination of picking and strumming? What rhythmic patterns are present in the picking and/or strumming pattern? Listen for overall tempo and tempo changes, if any.

Record Yourself: This way, you’ll be able to hear when you sound awesome and why. You can pinpoint areas where you can improve. In the case of songwriting, I recommend recording your ideas so you can step out of yourself a little bit and see the forest for the trees. Listen to your song structure or transitions, chord changes or tone, or whatever it is you feel you need to work on. Recording myself was especially helpful to me in the case of singing while playing guitar, and singing in general.

Educate Yourself: Though it is not necessary to be formally educated in music, it is so helpful to learn as much as you can about the subjects that you love. For example, I never received a formal education in guitar theory or performance, but studying piano, voice, music theory, and so much more, really have helped me to understand different aspects of music I may have guessed at before but couldn’t put my finger on.

Listen to what you love and keep playing: When it really comes down to it, ear training begins with listening to music! I like listening to whatever I’m into over and over again, simply because I love it, and because I realize there’s something I want to learn from it.

Once you start learning parts from songs with fuller instrumentation, it is really important to be able to distinguish the timbre, or distinct sound, of different instruments (which one is the guitar, the bass, the drums, the back-up vocals, the main vocals, etc). This way, you can more easily hear details about what each instrument is doing and how the instruments are interacting with each other. There are plenty of ear training tutorials on the Internet, but I assure you, you can still learn all these listening skills without it, if you want. Just keep on listening and figuring out what you like about what you love! And keep on playing!

I find it really difficult to throw things away. I endow inanimate objects with backstory and feelings.

The toaster will break. I will get a new toaster. And then I pause… I imagine all the hard toasting work the old one has done for me and I feel guilty about callously dumping it and consigning it to a lonely, unloved existence with other broken appliances. You feel sad now don’t you? Or maybe you’re wondering why I have been allowed to write another article for She Shreds?! Stay with me…

When it comes to guitarists and their guitars, I’m not alone in feeling a disproportionately strong connection with my instrument. While some just wouldn’t understand—It’s just a lump of wood and strings—most of you, I would expect, feel that your guitar is much, much more than that. Sometimes when I’m nervous my guitar is my anchor, it’s familiar weight is reassuring; other times, when I’m defiant, it’s my weapon, wielded with passion and fury. It’s my most valued possession and not because it cost a lot but because it’s my partner in crime.

This begs the question why do our guitars elicit such strong feeling? Surely the answer is in our passion for music itself. As a creator, your guitar is your co-author and your inspiration; its voice can define the tone of the song and lead you towards magical happy accidents or allow you to manifest the intangible ghost of an idea in your head into something that lives outside of yourself. It is a conduit between imagination and reality; a divining rod to the mysterious world of music itself. We love music above all else and our guitar gives us access to that music.

Patti Smith has Bo. A beaten up, black Gibson acoustic, 1931 Depression Model that her then-partner Sam Wagstaff gifted her. She fell in love with it when she saw it hanging in a shop; it was beat up and rusty, hanging forlorn alongside newer, flashier models. In her dazzling novel Just Kids, Patti writes, “… something about it captured my heart. I thought by the looks of it that nobody would want it but me.” (it does make me feel a bit better that Patti Smith also anthropomorphized inanimate objects…) “Bo which I still have and treasure,” she writes, “became my true guitar. On it I have written the greater measure of my songs.” The connection runs deep. In Patti’s hands, Bo transforms from wood and metal to be a snarling conduit for her punk poetry.

Photo by Rupert Hitchcox

Photo by Rupert Hitchcox

Willie Nelson has “Trigger,” a Martin acoustic that he got in 1969. It has a hole in the body from his picking style, hundreds of famous signatures on its soundboard and its own Wikipedia page. “When Trigger goes, I’ll quit” Willie famously grumbled. A partnership that has lasted a lifetime. Another guitar gifted with a name is Lucille, B.B. King’s Gibson. A fire broke out at a show he was playing and he risked his life to save the instrument. He found out later that the fire was caused by two men fighting over a woman named Lucille, so he named the guitar to remind him to never do two things: fight over a woman or run into a burning building to save a guitar (you would though, wouldn’t you?).

If you’re a She Shreds devotee, then you no doubt will have seen that Annie Clarke took it one step further: she birthed her own instrument. Made to fit Annie’s body, playing style and aesthetic preferences, the Ernie Ball St. Vincent guitar is twin to Annie herself. A mark of true brilliance, I think, is those guitarists who make their instrument an extension of their body. They make it speak, as it were, with their voice. Annie becomes as one with her guitar on stage and it’s lovely to see.

So, my own guitar love story: The first electric guitar I bought was a Yamaha RGX42ODZ. With a name like that (Yamaha laugh in the face of Romance!), it was never going to be the one. It had a Floyd Rose so I could be like my heros Eddie Van Halen and Steve Vai. I enjoy the thought of me going to Vibes, the local guitar shop (it didn’t have much of a vibe, to be honest), as a small 13-year-old girl and choosing a shredder’s guitar. It was a toss up between that and an Epiphone Les Paul Zakk Wylde Bullseye custom. The Yamaha was not the one, but you know what they say, you’ve got to kiss a load of frogs or something…

And it did happen. I had not been in London long, my student loan was burning a hole in my bank account, and I had been scouring Denmark Street eager to buy an electric guitar. I found a 1961 Hofner Verythin on, of all places, Gumtree (ask any London band where they met and they’ll give you a mysterious story, but we all know it was on Gumtree…) It was just beautiful. All original parts, except the tuners, and at a price I couldn’t quite believe. It was being sold by a man named Bill.

I bombed down to Hove and pulled up outside a big, detached house. I rang the doorbell. Bill was a charming, Hofner collector with a vast collection, endless information and stories, and an absolute sweetheart of a wife, June. I found out, over tea and cake (British people conduct all important business over tea and cake) that he had been a prop builder and had built Babe the Pig when they needed a less unpredictable electronic pig for the tricker scenes. But I digress!

Photo of Kitty Arabella playing the Hofner Verythin by Scott Chalmers

Photo of Kitty Arabella playing the Hofner Verythin by Scott Chalmers

Much like Patti with Bo, I knew it was my guitar. It was just perfect. Perfect in all it’s imperfection. It’s quirky noises and string buzz only add character to it’s dreamy sound: full and resonant with that pure 60s chime. It’s got two mini-humbuckers and, because it’s broken, changing between them does very little now. But I like that: it is what it is and I have to make it work. It really is very thin, like ridiculously thin and light, when you first pick it up it feels like it might snap in two but I’ve done some truly horrible things to it on stage (and played some pretty nasty fuzz through it) and it’s been remarkably resilient for something that is over fifty years old. I love that it’s old and battle scarred. I always think of the lives that it’s passed through and the journey it must have had to reach my hands today; it’s battled to survive the scrap heap. And I’m giving it my own scars.

This article, I guess, is a love letter to my guitar. And even though I did recently buy a brand new silver sparkly Danelectro because it looks like a guitar from 60s space films, you, Hofner Verythin, will always be my one true love. Guitars come and go, but when you find the one you know you won’t part with it. If you’ve loved and lost, you have my sympathy. If you’ve not found the one yet, it’s out there friend! You’ll know it when you play it.

Kitty Arabella Austen is a guitarist/vocalist for London blues rock band Saint Agnes.

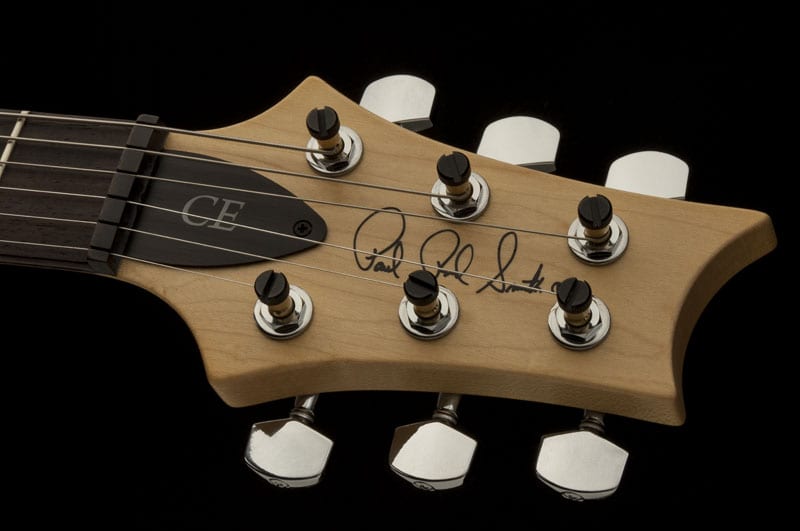

In 2008, production of the CE was halted. With a list of noteworthy updates, the CE 24 is back after almost ten years, accompanied by a PRS guarantee that it is “back and better than ever.”

Swoon Factor

With an immaculate ruby red finish on a flamed maple top, it is hard to keep your eyes off of this instrument. PRS went with very classic details such as vintage style control knobs and a cream selector switch. The white pickup rings transition nicely into the iconic bird fingerboard inlays. The original CE donned white dot fret markers, so seeing the birds in a rich indian rosewood on this model is definitely an improvement. Minor details on this guitar such as satin saddles resting on a polished chrome bridge make this guitar a uniquely aesthetic success.

Quality Control

To be completely honest, the price point of most PRS guitars deterred me from ever test-driving one. After giving this model a spin, I am happy to report that I feel like the price matches the quality. I absolutely love the feel of the hardware on this guitar. The locking tuners are particularly worthy of note. At close inspection, it is obvious that every component on this guitar, even down to each strap button, has been designed and manufactured to be highly functional as well as durable.

Shredability

With a scale length of 25”, the CE 24 stands right in between its classic contemporaries, the longer Fender Stratocaster (25.5”) and the shorter Gibson Les Paul (24.75”). As someone who generally plays the longer Stratocaster or Telecaster, the CE 24 is surprisingly comfortable. The appropriately placed curves form to my body perfectly, and the cutaway makes for an easily accessible 24th fret. The PRS pattern thin neck shape really lends to fast fingering and mobility which seems to be the key reason why this guitar is so easily playable. Another pleasantly surprising feature is the PRS-designed tremolo. It is extremely responsive and easy to control. From ripping solos to finger picking, this instrument makes it easier to do it all.

Sonic Impact

With a total of six possible sounds, the CE 24 is equipped with two PRS 85/15 pickups (a treble at the bridge and bass at the neck), a 3-way toggle switch, and volume and push/pull tone control knobs. The most desirable aspect of these controls is that you can switch from double to single coil position. The 85/15s are capable of pulling out very clear and consistent tone with a lot of sustain. With a developed, multifaceted design, I highly doubt there is a style of music that this guitar could not produce.

As a newcomer to the world of PRS, I am completely sold on the versatility and quality of the CE 24. If you are on the hunt for endless tone options and value beautiful design, look no further; the CE 24 might just be your new favorite axe.